Amazing Artist

She tried for years to ignore the voice inside that told her she was meant to be an author – in her New York society world, conformity was prized over creativity. When she found the courage to write, her short stories about people who were craving greater meaning in their lives resonated with so many readers that she finally believed in her own power to create and be free. Step back in time to 1921 and win the Pulitzer Prize for Best Novel with Edith Wharton…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

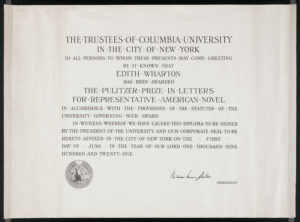

Edith Wharton didn’t expect her novel, The Age of Innocence, to win the 1921 Pulitzer Prize. The Prize was founded by Joseph Pulitzer, who created an endowment in his will for annual literary awards, including one for the “American novel published during the year which shall best present the whole atmosphere of American life and the highest standards of American manners and manhood.” It was a relatively new honor – since 1917 – and many excellent novels had been nominated.

Edith set The Age of Innocence in the 1870s New York high society of her childhood, when descendants of families who had established fortunes as bankers, merchants, or lawyers lived lives of leisure. It was an exclusive community that enforced its rituals and manners ruthlessly, and Edith’s mom was an enthusiastic guardian of the “old money” ways. Members were constantly on high alert for signs of “ill breeding” and any social faux pas or corrupt business dealing meant certain exile.

Edith decided to set her latest story in the past to escape her present feelings of loss in the aftermath of World War I and the death of one of her best friends, author Henry James. Her main character, Newland Archer, was like many men she had known who never questioned the expectations of society, including getting engaged to the “right” woman. But when Newland’s fiancee’s cousin arrives in town and proceeds to live by her own rules, he questions his own choices and has to choose between two worlds.

This tension between the expectation of conformity and the desire for a more meaningful life was a recurring theme in Edith’s work. She had struggled with it personally for years, until, as she described it, she finally acquired a personality of her own. This happened in 1899, when she published her first volume of short stories, The Great Inclination. Seeing her stories in a bound volume finally persuaded Edith that she was an author whose writing was “worthy of preservation.” She never again questioned that “story-telling was my job.”

This tension between the expectation of conformity and the desire for a more meaningful life was a recurring theme in Edith’s work. She had struggled with it personally for years, until, as she described it, she finally acquired a personality of her own. This happened in 1899, when she published her first volume of short stories, The Great Inclination. Seeing her stories in a bound volume finally persuaded Edith that she was an author whose writing was “worthy of preservation.” She never again questioned that “story-telling was my job.”

Ironically, her confidence as a writer was strengthened by a bad review of The Great Inclination. The critic declared that Edith wasn’t a skilled writer because all short stories must start with dialogue, and hers didn’t. Edith couldn’t reconcile his idea that every story in the world must follow the same fixed formula with her belief that writing is a personal work of art. She vowed then and there to “never to let my inward conviction as to the rightness of anything I had done be affected by outside opinion”

As a result, Edith wasn’t overly affected when, over 20 years later, controversy erupted after her Pulitzer Prize win. Two Pulitzer jurors publicly declared that they had voted to give the award to Sinclair Lewis’s Main Street, but were overruled by the Pulitzer Board of Directors. They further claimed that the Board changed the Pulitzer standard to give the Prize to the novel that best presented the “wholesome atmosphere” of American life in order to justify Edith’s win.

Edith was amused by the Pulitzer Board thinking The Age of Innocence was more wholesome than Lewis’s satire of the Midwest, because she had taken a similar sharp eye to New York society. She wondered if the same nostalgia she felt when choosing the era led the Pulitzer Board to overlook its sharp edges, or if they were fooled by the word “innocence” in her title.

Edith was amused by the Pulitzer Board thinking The Age of Innocence was more wholesome than Lewis’s satire of the Midwest, because she had taken a similar sharp eye to New York society. She wondered if the same nostalgia she felt when choosing the era led the Pulitzer Board to overlook its sharp edges, or if they were fooled by the word “innocence” in her title.

Sinclair Lewis sent Edith a gracious note congratulating her. He told her he was a fan of her work, having first read her novels in college. She responded that “when I discovered that I was being rewarded – by one of our leading Universities – for uplifting American morals, I confess I did despair.” She added “when I found the prize should really have been yours, but was withdrawn…disgust was added to despair.” She then invited Sinclair and his wife to visit her in France. After their visit, Sinclair dedicated his novel 1922 Babbit to her.

The Power of the Wand

2021 is the 100th Anniversary of Edith Wharton’s Pulitzer Prize win for The Age of Innocence. When Edith wrote it, she asked a good friend, who also had grown up in New York society to read it before she sent it to her publisher. He enjoyed it but told Edith that in his opinion, “we are the last people left who can remember New York and Newport as they were then, and nobody else will be interested.” Edith wasn’t offended – she agreed! And was very surprised when the book became a best seller. It still is widely read today and has also been adapted into movie, television, and theater versions.

Want to win a Pulitzer someday? Aspiring writers should check out the Bennington College Young Writer Awards, an annual context for high school writers to submit their work in Poetry, Fiction, or Non-Fiction. Its winners have gone on to win 12 Pulitzer Prizes!

Her Yellow Brick Road

Edith with one of her beloved dogs in 1889.

After her marriage, Edith felt trapped. Her struggle to reconcile her inner desire to be an author with her outer façade as a society wife led to a variety of health problems. Desperate to feel better, she gave herself permission to write. She worked with an architect on a non-fiction book about home design called The Decoration of Houses (1897). Edith had always been intrigued by how home décor and clothing defined people and societies, like the heavy curtains in parlors that mirrored the veils women wore outside to preserve their complexions. These gentle observations became her first public critiques of New York society rituals.

The book inspired Edith to create a home and garden that suited who she really was. In 1901, she and Teddy purchased 100 acres of land in the Berkshire area of Massachusetts. Edith had fallen in love with English manor houses and European gardens during her travels and worked extensively with architects and designers to design her own version. She named her home The Mount, and it became her favorite place to write.

Edith designed The Mount and considered it her first real home.

Edith published some new poetry, and then wrote several short stories about people trapped by marriage or circumstance in lives they didn’t want. Scribner Magazine published her work, and Edith discovered an audience hungry for her honest portrayal of human nature. She collected her and collected her favorites to be published together in book form. She reveled in the success of The Great Inclination– she had much fun with her experience in a London bookstore. When she asked the shop owner for something new and interesting, he handed her a copy of her own book, without knowing she was its author!

Once she believed in her power as an author, Edith’s world got bigger. She began seeking out literary circles to find others who shared her interests. She felt more confident, less shy, and ready to take on the challenge of writing a novel. Her first, The Valley of Decision was published in 1902. It was Just a few years later that The House of Mirth (1905) became a best seller and made her a literary star. Edith happily spent her profits on projects at The Mount.

Henry James, Edith, & Howard Sturgis at The Mount

Among her crowd, Edith’s success was something to be tolerated and not celebrated. Edith was a rebel – she joked that writing “regarded as something between a black art and a form of manual labor.” She got used to the comments from family and friends that her characters did too many improper things. Ironically, their criticism actually encouraged her, because it meant she was writing about real human nature and just the outer façade. Her novels were filled with characters leading double lives or hiding secrets. There were lonely children, questionable parentage, undereducated girls, tough mothers, and absent fathers.

Edith’s new identity as an author and Teddy’s worsening mental health put immense strain on their marriage. Teddy was more comfortable with their old society and didn’t like her new literary friends. As Edith was writing Ethan Fromme (1911), another story about being trapped in an unhappy relationship, she decided to set herself free. As her novel became another bestseller, Edith made arrangements to sell The Mount and start divorce proceedings. While most of her characters social pressure too difficult to resist, Edith was reconciled to leaving it behind to build a career for herself as a writer.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Edith grew up in a wealthy and socially influential New York City family. Her great-aunts were said to be the namesake of the phrase “keeping up with the Joneses.” Edith’s brothers were 16 and 12 when she was born, so for most of her upbringing, she was the only child at home.

Portrait of Edith when she was about 8.

Her family divided its time between the city and a summer home in Newport, Rhode Island until Edith was 4 and they moved to Europe. Around the same age, Edith invented a game she called “making up” where she walked around with a book, turned its pages, and made up a story about someone she had seen on the street. Edith’s dad taught her to read the books she carried around but she still kept “making up.”

Edith and her family returned to New York in 1872, when she was 10. Edith felt like a stranger in the city and preferred her summers in Newport, where she could be outdoors swimming and boating. Her parents jumped right back into their very structured lives and Edith’s mom began drilling her on the social rules she was expected to follow. Appearances were very important, and Edith learned early how houses, clothing, and manners define a society and a family.

In New York, wealthy girls didn’t attend school, but had private tutors who taught them “appropriate” subjects. Edith also was forbidden from reading contemporary novels because her mom thought they were inappropriate for an unmarried girl. Edith grew restless with the limits put on her education and found a solution just down the hall in her father’s personal library. By her teens she knew the 700-800 books there by heart.

The classic literature, plays, and poems Edith devoured inspired her to trying writing stories herself, on brown parcel paper she saved from packages. She found inspiration by watching the beautiful people of Newport. On the outside their lives were a constant whirl of boat races, tennis games, social calls, and dinner parties and discussion of potentially dangerous subjects like politics, religion, and relationships was not allowed. Edith wondered if their outward devotion to rules and propriety matched their inner lives and thoughts. She wrote a short novel, Fast and Loose, about this idea when she was 15.

Portrait of Edith at age 19.

Her parents were mostly indifferent to her hobby, but did arrange for a book of her poems, titled Verses, to be privately published when she was 16. But then they told Edith that they wanted her to start the process of finding a suitable husband, and arranged for her to make her formal entry into society at 17, a year early. Edith was tossed into a world of dinners, theater, and dances. She was surprised at how much she enjoyed it, although she also missed having time to write, especially when a family friend, the famous poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, read her poems and arranged for five of them to be published in the Atlantic Monthly magazine the following year.

After a broken engagement to a man whose mother didn’t approve of Edith’s intellect, Edith married a friend of her brother’s named Teddy Wharton. He was 13 years older than her, from a prominent Boston banking family, and lived a life of leisure paid for by his trust fund. Edith was now on path to live the same life as her parents, with homes in New York City and Newport. The daily social rounds gave her little time to read and write.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Edith Newbold Jones was born on January 24, 1862.

- Edith loved dogs. She got her first one when she was 3 and had at least one pet dog most of her life.

- When Edith was 9, she contracted typhoid fever and almost died. She was left with unresolved fears from the experience. For years afterward, she needed her light on and a maid with her in order to fall asleep. She also pointed her slippers in the same direction every night to keep “hobgoblins” away. As an adult, she wrote many ghost stories as a way of processing the isolation and fear she felt. Some of her best have been collected in The Ghost Stories of Edith Wharton. Edith often said she didn’t believe in ghosts, but was scared of them anyway.

- Edith married Edward (Teddy) Wharton on April 29, 1885. They were married for 28 years.

- Edith was traveling in Europe when World War I began. She stayed in France for its duration and became very involved in the French war effort. She founded two organizations to help civilians caught up in the destruction – the Children of Flanders and the American Hostel for Refugees. She also published articles encouraging the United States to enter the war on the Allied side, and raised funds through the sale of The Book of the Homeless (1916), an anthology of war essays and stories by well-known authors. For her efforts, Edith was awarded the French Legion of Honor.

- After the war, Edith decided to make France her primary residence. She bought two homes in France and when she wasn’t writing, could be found working in her gardens or hosting salons where the literary community could gather. She returned to the United States frequently enough to avoid losing her American citizenship.

- In 1923, Edith became the first woman to receive an honorary doctorate from Yale University. Edith bequeathed her personal papers to Yale, with the condition that some of them be kept private until 1968.

- In 1930, Edith became the first woman elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1930.

- Edith didn’t start writing as a vocation until she was 35. She published almost a book per year until her death at age 75 on August 11, 1937. She authored 48 books, in addition to numerous poems and short stories.

- The Mount has developed a reputation as a haunted house. Some claim you can hear Edith’s housekeeper’s footsteps in the marble hallway. The house became an all-girls school in the 1940s and then housed a theater company lived in the 1970s. It is now open for tours, included a ghost tour.

Want to Know More?

Wharton, Edith. A Backward Glance: An Autobiography (Scribner 1998).

Lee, Hermione. Edith Wharton (Vintage 2008).

Jones, J. Nicole. “Ghost Hunting With Edith Wharton” (The Paris Review Oct. 31, 2019).

Masters, Kristin. “Edith Wharton, Sinclair Lewis, and a Pulitzer Kerfuffle.” (Books Tell You Why May 21, 2019).

Pride, Mike. “Edith Wharton’s ‘The Age of Innocence’ Celebrates It’s 100th Anniversary” (Pulitzer Files).

Staff. “A Controversial Prize Brings Edith Wharton & Sinclair Lewis Together” (Library of America Blog (June 28, 2011)