Amazing Artist

She traveled over 17,000 miles to take more than 4,000 photos documenting The Great Depression. Her childhood battle with polio gave her an understanding of suffering, and her compassion for the people she photographed is evident in every image. She took the most iconic photo of the era after driving 20 miles past a sign for a Pea-Picker Camp, listening to the voice in her head telling her to turn around, and returning to bear witness to those who lived there. Walk into a 1936 California migrant labor camp and meet Dorothea Lange…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Dorothea Lange just finished a field assignment for the Farm Securities Administration. She had been on the road for about a month and was anxious to get home. It was March, 1936 and America was in the middle of the Great Depression.

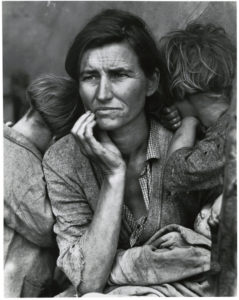

“Migrant agricultural worker’s family…” by Dorothea Lange, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Dorothea drove along a rural road near Nipomo, California when saw the sign for a Pea-Picker Camp out of the corner of her eye. For the next 20 miles, she couldn’t stop thinking about that sign. So Dorothea finally listened to her intuition, turned around, and drove back to investigate.

Dorothea parked her car and stepped out into the rain. She talked with a group of workers standing around — the pea crop had been ruined by the freezing temperatures so there was no work. And there were about 2,500 people living at the camp, with no way to earn a living.

Many of the families had traveled to California in search of work. They lost their farms during the Dust Bowl. And they left the Great Plains with nothing but the clothes on their backs. They were desperate, homeless, and starving.

As Dorothea walked into the campsite, she was immediately captivated by a mother and her children sitting under a tarp. She grabbed her camera and struck up a conversation with the woman, Florence Owens Thompson.

As Dorothea walked into the campsite, she was immediately captivated by a mother and her children sitting under a tarp. She grabbed her camera and struck up a conversation with the woman, Florence Owens Thompson.

Dorothea learned that Florence was a 32 year old single mother with seven children (her husband had died from tuberculosis a few months earlier). She moved from farm to farm in search of work. The family was barely surviving, eating frozen vegetables and birds that were caught by her kids.

Florence requested that Dorothea not publish her name in connection with either the story or photos. As a result, no one knew the name of the woman in Dorothea’s famous photograph for 42 years (until 1978).

Dorothea was at the camp for about 10 minutes and took seven shots of Florence and her children, each closer than the previous one. Then she raced home to develop the film. And she gave two photos to the editor of the San Francisco News. She knew they were powerful images and hoped that an article could spread the word about the terrible conditions at the camp.

“Migrant Mother,” by Dorothea Lange, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

A few days later, on March 10, 1936, Dorothea picked up the morning edition of the San Francisco News. She looked at the front page and saw two of her own photographs staring back at her. A smile grew on Dorothea’s face as she read the article, which described the plight of the day laborers at the Pea Pickers Camp and announced that the federal government was sending 20,000 pounds of food to the camp. She was so relieved that the people she met a few days earlier wouldn’t starve. And her photos helped to make that happen.

The last of the seven photographs taken by Dorothea at the Pea Pickers Camp became the most famous work of her career — Migrant Mother. It also became an iconic image of the Great Depression. Since Dorothea worked for the federal government at the time, the image was in the public domain and she never held its copyright. Anyone could publish Migrant Mother at no cost. And they did. In fact, Migrant Mother is one of the most reproduced images in American history.

The Power of the Wand

Dorothea was a pioneer in the field of documentary photography. She sought to capture everyday life, highlight social issues, and influence public policy. She documented the suffering of people across America. And her photographs became the face of the Dust Bowl and Great Depression.

Today, many women and girls follow in Dorothea’s footsteps and use the power of art to advocate for social justice. For example, Las Fotos Project is a nonprofit organization in California that uses photography to help teen girls find their voice. Most of the girls who participate in the program are ages 13-18 from communities of color in the Los Angeles area. Since it was founded in 2010, Las Fotos Project has helped hundreds of teen girls develop skills, build their confidence, and become advocates for their communities.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Dorothea was determined to become a photographer. She moved from job to job, teaching herself all aspects of the business. Eventually, Dorothea opened her own portrait studio in San Francisco. She became known for her relaxed compositions and use of soft focus to portray a person’s best features. Before long, her studio was a gathering place for the bohemian crowd and artists in San Francisco.

Then, the stock market crashed in 1929 and her work dried up — no one had the money to commission portraits anymore. So Dorothea sat at the window of her studio and watched the people in her neighborhood. Everyone seemed lost, in addition to being homeless, jobless and hungry.

Then, the stock market crashed in 1929 and her work dried up — no one had the money to commission portraits anymore. So Dorothea sat at the window of her studio and watched the people in her neighborhood. Everyone seemed lost, in addition to being homeless, jobless and hungry.

So Dorothea decided to shift the focus of her work — she felt compelled to go into the streets and document the suffering of the Great Depression. At the same time, she had a deep respect and compassion for those she photographed. She looked for people’s courage and dignity in the face of hardship. And Dorothea wanted to tell the stories of those she photographed, so she interviewed them and wrote down quotes whenever possible.

“White Angel Breadline,” by Dorothea Lange, National Archives

Dorothea regularly displayed her photographs in her studio and solicited feedback from visitors. Then, she exhibited her street photography at a gallery in Oakland in 1934. And her work caught the eye of many people (including her future husband, Paul Stryker). One of her first photographs, White Angel Breadline, became instantly famous.

The work was tough on Dorothea, emotionally and physically. She defied the gender norms of the day and put her work first, sometimes at the expense of her marriage and children. She could be intense and had incredibly high standards for her work — many times, she told herself “Not good enough, Dorothea.”

Dorothea photographed the suffering of people in almost every state of the Union during the Great Depression. She and her second husband, Paul, worked together to document the plight of migrant workers, sharecroppers, and farm families throughout the Great Plains and the West. In total, she traveled over 17,000 miles and took over 4,000 photographs while she worked for the federal government.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Dorothea had personal experience with hardship at an early age — she came down with polio when she was 7 years old. It was very painful and permanently damaged her right leg and ankle. As a result, she walked with a limp for the rest of her life. She was called “Limpy” by the neighborhood children and felt ostracized while growing up.

During her childhood, Dorothea spent much of her time observing people — a skill she drew upon in her professional life. She went to school on the Lower East Side, while her mom worked at a New York public library nearby. After school, Dorothea spent time at the library until her mom got off work. She spent most afternoons watching the activities in the immigrant neighborhood from the library windows. She learned how to watch people without being intrusive (which was helpful when she was a photographer).

During her childhood, Dorothea spent much of her time observing people — a skill she drew upon in her professional life. She went to school on the Lower East Side, while her mom worked at a New York public library nearby. After school, Dorothea spent time at the library until her mom got off work. She spent most afternoons watching the activities in the immigrant neighborhood from the library windows. She learned how to watch people without being intrusive (which was helpful when she was a photographer).

Dorothea wanted to be a photographer, even though she had never held a camera. After high school, she worked for a number of photographers in Manhattan and took a photography class at Columbia University. Then, she bought a camera and converted the chicken coop at her mom’s house into a dark room.

When she was 22 years old, Dorothea and her friend decided to travel around the world (with only $140 between them). They took a ship from New York City to New Orleans, then a train to the West Coast. Their money was stolen, however, when they arrived in San Francisco.

The very next day, Dorothea got a job at the photography counter of a dry goods store. She also joined the San Francisco Camera Club, which gave her access to a dark room. And she began to experiment with different angles and exposures in her photographs.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Dorothea was born May 26, 1895 in Hoboken, New Jersey. She had a younger brother. Her father left when she was 12 years old and they lived with her grandmother. Dorothea dropped her father’s name when she began her photography career.

- Dorothea married a Western landscape painter named Maynard Dixon in 1920, who was almost 20 years older than she. They had two sons (Daniel and John), then divorced 10 years later.

- Dorothea married Paul Taylor a few months after her divorce. He was a social science professor at UC Berkeley and they worked on many projects together over the years.

- Dorothea spent most of her career working for a number of government agencies — Rural Workers Association, Resettlement Administration, Farm Security Administration, US Bureau of Agricultural Economics, War Relocation Authority, and the Office of War and Information.

- During World War II, Dorothea was hired to document the forced evacuation of Japanese-Americans to internment camps right after Pearl Harbor. Dorothea followed Japanese-Americans as they sold their belongings, closed their businesses, and packed their necessities. She documented their arrival at assembly stations and transport on trains. Then, she spent some time at the camps themselves.

- Dorothea partnered with Ansel Adams to document life during World War II in the Bay Area. He called Dorothea “both a humanitarian and an artist.”

- Dorothea experienced a number of health problems after World War II, including a severe ulcer and esophagitis.

- Dorothea took a number of assignments for Life Magazine later in her career. And she co-founded the photography magazine, Aperture.

- Dorothea was honored with an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1966. She spent 2 years preparing for the exhibit, which included 200-250 of her photographs. She died within weeks of choosing the final photos for the exhibit.

- Dorothea died from cancer on October 11, 1965 in San Francisco.

- Migrant Mother was named by Time Magazine as one of the 100 “Most Influential Images of All Time.”

- Dorothea received a number of awards for her work, including:

- Guggenheim Fellowship for Creative Arts in 1941 (the first woman photographer to receive the fellowship)

- International Photography Hall of Fame in 1984

- National Women’s Hall of Fame in 2003

- California Hall of Fame in 2008

Want to Know More?

FSA Photo Collection at the Library of Congress.

Elliott, George. Dorothea Lange. (New York: MOMA, 1966).

Gordon, Linda and Gary Okihiro. Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, reprinted in 2008.

Gordon, Linda. Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2010.

Lange, Dorothea and Christopher Cox. Dorothea Lange. New York: Aperture, 1987.

Lange, Dorothea and Paul Taylor. An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion. New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1939.

Lange, Dorothea and Elizabeth Partridge. Dorothea Lange: A Visual Life. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994.

Meltzer, Milton. Dorothea Lange: A Photographer’s Life. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2000).

Meister, Sarah Hermanson. Dorothea Lange: Migrant Mother. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2019.