Passionate Patriot

She used her charm, intellect, and genuine interest in people to lay the foundation for a tradition of fellowship and bipartisan conversation that is uniquely American. She realized the power that can come from conversation and common ground, especially if it can happen over a delicious treat like ice cream! Travel back in time to the 1814 White House sitting room and meet Dolley Madison…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Dolley in her 40s, when she was First Lady

First Lady Dolley Madison was pacing back and forth in her drawing room. It was August 24, 1814 and the War of 1812 had already outlived its name by more than two years. Dolley was waiting for news about the 4000 British soldiers had gathered in Maryland, not far from the new American capital of Washington City.

Dolley’s husband, President James Madison, had gone to the front lines to assess the threat level. Dolley stopped to look out the window and watched those who had already taken to the dusty roads with their belongings leave the city. She then went up to the roof to look through her spyglass to see if she could spot James or the British. So far there had been no sign of either.

Dolley knew that the British officers had a personal interest in destroying the capital. Many of them still felt the sting of losing to the colonies 20+ years ago. They also wanted revenge for the American burning of the Parliament building in Ontario, Canada the year before. Their goal was not just to defeat, but to humiliate the United States.

Photograph of Dolley and James Madison.

Dolley thought about how, before James left, he asked her if she had “the courage and firmness” to remain at the White House. Dolley told him she did. Although he initially wasn’t overly concerned, once he saw the massive British presence, James sent Dolley a message to be ready to evacuate at “a moment’s notice.” Dolley started packing – not her own belongings, but instead the important government papers papers that would be disastrous to land in enemy hands. She filled as many trunks as could fit in her carriage with documents.

As Dolley walked through the White House, she peeked into the dining room to see how the preparations were going for the dinner party Dolley and James planned to host that evening for a collection of government officials and prominent citizens. James had asked Dolley not to cancel it until it was absolutely necessary. The current war had divided Americans, leaving many angry with James. For years, James had relied on Dolley to use her talent for entertaining and conversation to foster connections between people. She created social settings where political discussions could be had amicably and compromises reached.

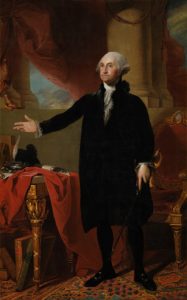

The Gilbert Stuart portrait of President Washington that Dolley saved from the British

As the President’s wife, Dolley had created a role for herself. She had hosted the first Inaugural Ball ever held in Washington City as her first step towards cultivating the “First Lady” role as a symbol of patriotism and unity. Dolley’s dinner parties were famous for extravagant ice cream desserts. Ice cream was a delicacy because it was so difficult to make and keep frozen and it made her guests feel special. When James was re-elected and she hosted her Second Ball, she made sure ice cream was on the menu.

Dolley looked at the beautifully set table and wondered if they would be able to enjoy their meal that evening. Washington City’s mayor had already stopped by twice to beg her to leave the city. She had refused, telling him that she wouldn’t leave without James or a message from him telling her to go. Around 3:00pm, that message came in the form of a handwritten note from James delivered by one of his men telling her that the British had attacked and were heading toward the city.

Time now was of the essence, but Dolley refused to leave until she could ensure the safety of the portrait of George Washington hanging in the State Dining Room. Dolley feared the damage to American morale if the British were able to claim General Washington’s portrait as a war prize. Dolley asked the few remaining servants to unscrew the bolts that attached the portrait to the wall, but it proved too difficult to do in a hurry. Dolley then told them to break the frame and just take the canvas to safety.

Time now was of the essence, but Dolley refused to leave until she could ensure the safety of the portrait of George Washington hanging in the State Dining Room. Dolley feared the damage to American morale if the British were able to claim General Washington’s portrait as a war prize. Dolley asked the few remaining servants to unscrew the bolts that attached the portrait to the wall, but it proved too difficult to do in a hurry. Dolley then told them to break the frame and just take the canvas to safety.

Dolley then got in her waiting carriage and left her home. She was just in time, as the British soldiers arrived not long afterwards. They sat down in the Dining Room to enjoy the meal that Dolley had planned for that evening’s dinner party. When they were done, they burned the White House to the ground. When Dolley reunited with James, they set up a temporary “White House” in the Octagon House. Dolley began lobbying to rebuild and keep the capital in Washington City.

The Power of the Wand

Ice cream made its first appearance in the United States colonies in the mid-17th century. After the Revolution, it became a special treat in the new Republic. The first ice cream parlor opened in New York in 1790. But it was Dolley who popularized ice cream as a patriotic treat.

Dolley served Ice cream molded into elaborate shapes like this (Colonial Williamsburg)

Dolley Madison used ice cream as diplomacy, serving it to her guests at the White House. It was difficult to make ice cream for large crowds because of the challenge of keeping it frozen. Blocks of ice had to be cut from frozen water in the winter and then kept in a special house under straw to keep it from melting. Making and molding the ice cream had to be done quickly for the same reason.

Dolley loved to experiment with flavors. A classic vanilla with fruit or sauce on top was considered very fancy because vanilla bean was expensive. Dolley also enjoyed ice cream with more savory flavors, like parmesan cheese, asparagus, or her favorite…oysters! And today, the average American eats 44 pints of ice cream annually, which adds up to $10 billion in sales a year!

Her Yellow Brick Road

When Dolley married John Todd when she was 22, she had no way of knowing that just 3 years later she would be a widow with a young son. A yellow fever epidemic swept through Philadelphia in 1793. John sent Dolley and their two children into the country to protect them, but when John joined them, he and their youngest son got sick and then died on the same day.

Dolley moved back to the city and spent much of her time at the boardinghouse her mom operated. New York Senator Aaron Burr was a frequent guest there, and his friend James Madison asked him for an introduction to Dolley. James was a Congressman from Virginia who was well-known for co-authoring the Constitution,. He also had a reputation as a brilliant and kind man. When Dolley and James married on September 15, 1794, Dolley had to make some major adjustments. First, she was no longer welcome in the Quaker meetings because she married outside of it. Second, she was going back into the farming/slaveholding world she had left when she was 15.

Portrait of Dolley at age 26

It was an unstable time for the United States, which was still in its infancy and the growing pains were becoming apparent. The Constitution was a huge experiment – no country had tried this type of government before – and now the Americans had to figure out how to actually execute it. People split into two political parties. The Federalists, led by John Adams and Alexander Hamilton, were typically from the north and east, wanted centralized power and fewer voters, and were criticized for acting like “aristocrats” but didn’t own slaves. Republicans like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison were generally from the south and west. They valued liberty over power, had a more expansive definition of who “the people” are, but were often slaveholders.

The first battle of Federalist vs. Republican came in the hard fought 1796 election. When Adams defeated Jefferson, James retired from Congress. He and Dolley moved to Montpelier, his Virginia estate, and lived a country life. When Jefferson won the 1800 election rematch, he asked James to be his Secretary of State. James agreed, and the family moved again – not back to Philadelphia, but to the new capital – a swampy piece of wilderness land between Maryland and Virginia named Washington City.

In the new capital, the location of the government buildings had been specifically planned and prioritized, so while the White House and Capitol were ready, there were many strange empty areas. With few homes, stores, restaurants, or pubs, the social opportunities were severely lacking. The politicians in town had little to do other than argue with each other.

When James and Dolley arrived in town, they temporarily moved into the White House with President Jefferson. Jefferson was a widower, so Dolley agreed to host some dinners for him so it would be socially acceptable for him to include women. Jefferson had brought a recipe back from his time in France for ice cream. Dolley started featuring it in her dinner menus because it made guests feel special. Ice cream was not just scooped, but frozen into elaborate shapes using molds.

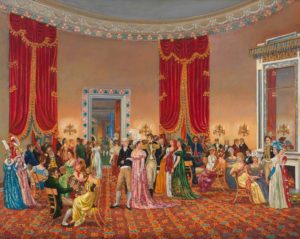

A look into one of Dolley’s White House Wednesday night socials

Dolley took advantage of social drought to create her own traditions and events to bring people together. She made a point of calling on different people every day and making sure she visited not just government officials, but local residents and foreign visitors alike. She made a name for herself as a charming conversationalist who wasn’t afraid to be herself – an outgoing girl raised in the country who loved fashion.

When James became President in 1809, Dolley started a tradition of hosting Wednesday night receptions at the White House. There was a standing invitation for the men and women of Washington City to attend these informal gatherings. Dolley spent her time circulating, introducing people, and adding a spark to conversations. She made a point of remembering people’s names and set an example of civility and bipartisanship by emphasizing what people had in common instead of what drove them apart. She didn’t talk politics, but knew all the political undercurrents and subtly lobbied those guests who could help her husband achieve his goals. Dolley, and as one of her admirers observed “a wish to please, and a willingness to be pleased.”

While some of her more snobby critics disapproved of how inclusive she was, Dolley didn’t care – she knew the shopkeepers and tradespeople were as important to the health and future of the country as the politicians and diplomats. And her gatherings were so filled with delicious food, drinks, and fun that even the snobs still attended so they didn’t miss out on anything.

But looming in the background were the continuing tensions with the British. They were still bitter about losing the Revolutionary War and wanted to assert their primacy. Tensions broke into war on June 18, 1812, James was re-elected to a second term a few months later, and Dolley hosted her second inaugural ball on March 4, 1813, where she made a point to serve ice cream to her guests.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Dolley’s parents were Quakers. Dolley’s mom since childhood and her dad converted when they got married. Her dad was a farmer whose livelihood depended on the unpaid labor of the enslaved. While Quakers believed slave owning was wrong, it was illegal in Virginia to free them. Her parents expected Dolley and her seven siblings to help with the farm work. She cooked, sewed, and when she was old enough, helped drive the plow.

Photograph of Dolley taken in 1848 when she was 80.

Quakers believed in educating their daughters as well as their sons, and Dolley loved to read and write in her spare time. But the Quakers also prized reserve in style and temperament, and Dolley’s flair for fashion and natural high spirits often got her disapproving looks in their community.

When Virginia finally changed its slavery law in 1783, Dolley’s dad freed their slaves, knowing that without their labor, he would no longer be able to support his family with the farm. They packed up and moved to Philadelphia, which was the bustling capital of the new republic. He opened a starch making business, and Dolley spent most of her teen years in the city.

Six years later, the business went bankrupt and Dolley’s dad was kicked out of the Quakers because they viewed business failure as a sign of bad character. Losing his place in the community sent him into a deep depression and he refused to leave his room. Dolley’s mom had to support the family and turned her home into a boardinghouse. Most of her guests were politicians in town for Congress. Her dad died three years later and by then, Dolley had married John Todd, a lawyer who the family had known for years.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Dolley Payne was born on May 20, 1768 in New Garden, North Carolina – a Quaker community.

- Dolley married John Todd on January 7, 1790. It was her father’s wish that they marry and Dolley, concerned for his health, agreed.

- Dolley had two sons: John Payne Todd (1792) and William Todd (1793).

- The Treaty of Ghent ended the War of 1812 on Christmas Eve 1814. Communication was slow and General Andrew Jackson fought the Battle of New Orleans two weeks later and won a decisive victory.

- Dolley and James returned to Montpelier in 1817. They spent considerable time curating James’ professional papers and writings. Congress bought these papers from Dolley in 1848.

- Dolley’s son Payne had many business and gambling debts. He spent time in a debtor’s prison in Philadelphia in 1830. After James died on Juen 28, 1836, Dolley split her time between Montpelier and Washington, D.C. until she had to sell Montpelier to help pay more of her son’s debts.

- In 1844, the House of Representatives gave Dolley a lifetime seat on the House Floor. They also gave her free postal privileges for her lifetime – an honor only ever given to George and Martha Washington

- Dolley died on July 12, 1849 at age 81. She was honored with a State funeral.

Want to Know More?

Allgor, Catherine. A Perfect Union: Dolley Madison and the Creation of the American Nation (Henry Holt & Co. 2006).

Krull, Kathleen. Women Who Broke the Rules: Dolley Madison (Bloomsbury 2015).

Scofield, Mary Ellen “Unraveling the Dolley Myths” (White House History Number 31 Summer 2012).

Staff. “Dolley Madison’s Life”(American Experience)

Yun, Molly. “Ice Cream: An American Favorite Since the Founding Fathers” (PBS).