Audacious Adventurer

A documentary about an adventurous Navy pilot inspired her to learn how to fly so she too could explore the world. But when her nearsightedness got in the way of that dream, she turned to her second love – writing – and became one of the most courageous and honest war correspondents in American history. Her reporter’s notebook and camera were her constant companions and her humor and bravery won the hearts of the troops she covered. She did what it took to report firsthand, including getting certified to jump with paratroopers in Vietnam. Climb up a 250 foot training tower at Fort Campbell in 1959 and meet Dickey Chapelle…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Early in Dickey Chapelle’s reporting career, one of her editors told her to “be sure you’re the first woman somewhere.” She thought about that advice as she climbed the 250 foot tower at Fort Campbell to make her first parachute jump. She was training with the 101st Airborne Division to be certified as a paratrooper, and if she passed, would be the first woman to do so.

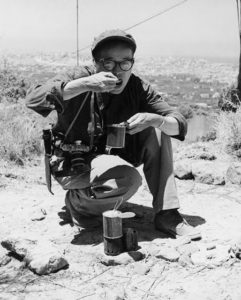

Dickey in 1958. This was her favorite photo of herself working. (WI Historical Society)

Dickey had been a war correspondent and photographer for nearly 20 years, since World War II. Most newsrooms had few women reporters and just a handful of those reported from the front lines. Dickey was often the only woman around, and at first glance was not an imposing presence. She was short and slight, with black rimmed glasses and ever-present pearl earrings, and got used to proving herself. Once when she was trying to sell a book on military training to a skeptical editor, she completed every requirement of the Army fitness test in his office. He agreed to buy the book.

Dickey firmly believed in only reporting what she witnessed firsthand. She worked to get military credentials so she could be embedded with troops. And she focused on capturing the moment without worrying too much about setting up the perfect photo.

Now it was 1959, and American troops were heading to Vietnam. Dickey intended to be there to document it. Vietnam’s difficult jungle terrain called for paratroopers. When Dickey first had the idea to accompany them, she wondered if it was crazy to start jumping out of airplanes at 41 years old. But her mission to be a witness to war overrode any caution, which is how she found herself at Fort Campbell.

Now it was 1959, and American troops were heading to Vietnam. Dickey intended to be there to document it. Vietnam’s difficult jungle terrain called for paratroopers. When Dickey first had the idea to accompany them, she wondered if it was crazy to start jumping out of airplanes at 41 years old. But her mission to be a witness to war overrode any caution, which is how she found herself at Fort Campbell.

Dickey started in ground school. She learned proper body position, what to do if things go wrong, how to land, and how to pack up the chute. She learned to keep her eyes open when she jumped – even though human instinct is to close them – because paratroopers need to constantly monitor their surroundings to avoid collisions or entanglements. She also had to fight the urge to immediately deploy the chute by counting to 6000 before pulling the cord.

Dickey on patrol in Vietnam (WI Historical Society)

Now that it was time to try her first jump, Dickey was ready. She reflected on the vow she made three years earlier, after she was taken prisoner by Russian soldiers while covering the Hungarian revolution. Knowing that the Russians often executed reporters as spies, Dickey hid her camera in a glove and threw it out the car window while being transported to a Budapest prison. She was there for nearly 2 months, mostly in solitary confinement with daily interrogations. After she was released, she vowed never to let fear deter her from action. From her perspective, the worst had happened and she had survived.

Dickey reached the top of the training tower and double checked her gear. She took a deep breath, walked to the edge, and jumped. As she descended, she realized another reason to keep her eyes open – to not miss a minute of one of “the greatest experiences one can have.”

The Power of the Wand

Dickey’s bravery and humor won respect from the troops she covered because she tried to view events through their eyes. She dug her own foxholes and carried her own gear. She viewed it as her mission to tell the story of the “men brave enough to risk their lives in the defense of freedom against tyranny.”

On November 4, 1965, Dickey was on patrol when a Marine stepped on a tripwire and triggered an explosion. Shrapnel hit Dickey in the neck. Another photographer captured a photo of a Navy Chaplain kneeling over her body to give her last rites. Dickey was the first American woman war correspondent to be killed in action.

On November 4, 1965, Dickey was on patrol when a Marine stepped on a tripwire and triggered an explosion. Shrapnel hit Dickey in the neck. Another photographer captured a photo of a Navy Chaplain kneeling over her body to give her last rites. Dickey was the first American woman war correspondent to be killed in action.

The Marines were Dickey’s favorite military branch to cover because “they taught me bone-deep the difference between a war correspondent and a girl reporter.” The Marines returned her affection and were devastated by her death, declaring that “she was one of us, and we will miss her.” A Marine escort flew her body home to Wisconsin. She was buried at Forest Home Cemetery with full military honors, which is rarely done for civilians.

Visit the Wisconsin Historical Society to see a collection of Dickey’s photographs.

Her Yellow Brick Road

When the United States entered World War II, Dickey’s husband Tony re-enlisted in the Navy to be a war photographer. His first orders sent him to Panama. Dickey wanted to go with him, but wives weren’t allowed, so she applied for and was granted her own military correspondent credential.

Dickey as a World War II correspondent (WI Historical Society)

Dickey spent most of her time in Panama covering Army infantry combat training for Look Magazine, scribbling her observations in her notebook and typing up her stories at night. They were in Panama for 9 months of 1942 until Tony was reassigned and Dickey returned to New York. Dickey spent the next two years trying to get another war correspondent assignment and writing several books about women in the workplace. Finally, in early 1945, an offer came through from Fawcett Publications, which owned several magazines. They wanted Dickey to travel to the Pacific to cover the war there. Tony tried to talk her out of it, but Dickey felt it was an offer she couldn’t – and didn’t want to – refuse. The Navy approved her trip, making her its first credentialed woman photographer.

Dickey arrived at California’s Alameda Air Station to report on Navy nurse training. Dickey then followed the nurses overseas, first to Guam and then to Iwo Jima on the USS Samaritan, a hospital ship. Iwo Jima was the bloodiest battle in Marine history and Dickey captured images of casualties being evacuated off the island. She asked for and was granted permission to go ashore so she could visit a field hospital. Her first date line from a war zone read: FROM THE FRONT AT IWO JIMA MARCH 5 – UNDER FIRE.

One of the photos Dickey took in Okinawa before it was discovered she had disobeyed orders and gone ashore (WI Historical Society)

After the positive response to her reports from Iwo Jima, the Navy realized Dickey’s photos could help the war effort. Blood donations from the public had declined but the need was growing, so the Navy assigned Dickey to another hospital ship, the USS Relief, to cover the use of blood donations on the ship to treat wounded troops. So in April 1945, she found herself on the way to Okinawa, a Japanese island recently invaded by US forces.

Dickey again asked to go ashore but this time was told no by the Admiral in charge of public relations for the Pacific fleet. Dickey restrained herself for two days before wrangling her way onto a landing craft going ashore. Upon arrival, she sought out a Marine officer and persuaded him that she could spur blood donations with photos to show how needed it was. Dickey spent 10 days with a Marine medical unit near the front lines. Her reporting had a big impact, but also revealed that she had violated the Admiral’s order. She was removed from the island, confined to house arrest on a Navy ship and lost her credentials. Dickey had to return home.

But Dickey wasn’t satisfied on the home front – there were too many stories to be told. While she was looking for an international assignment, she wrote a story for Seventeen magazine about a Quaker youth camp in Kentucky dedicated to peace. This job led to more assignments from Quaker relief agencies – and eventually the U.S. Department of State – to cover the rebuilding of post-war Europe.

Dickey receiving the George Polk Memorial Award in 1962 (Overseas Press Club of America)

Dickey and Tony spent the next 6 years living out of a truck as they visited more than 20 countries. In 1949, they created their own relief agency, the American Voluntary Information Services Overseas (AVISO), with Dickey sadly observing that “the magnitude of relief devised never matched the magnitude of suffering caused.” Their photos attracted the attention of editors at the prestigious National Geographic magazine who published two photo essays of their work in 1953 and 1956. But this professional success could save their crumbling marriage. They returned to New York and got divorced.

Now that she was on her own, Dickey wanted to be embedded with the military again. She called the Marine officer who had allowed her into the Okinawa medical unit. He was now Commandant of Marine Corps and helped her get her credentials back. Dickey spent the next several years documenting the human cost of war. She covered over 30 fighting forces by 1959, including the Marine occupation of Lebanon and the Algerian revolution. When she asked the rebels who smuggled her into Algeria why they asked her to tell their story, they replied that she was the only one willing to go.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Dickey as an aspiring pilot (WI Historical Society)

Dickey – known as Georgie Lou until her teens – grew up in Wisconsin. Her parents were ardent pacifists who raised Georgie Lou and her younger brother without many rules. Their permissive approach was intended to encourage their children to listen to their own consciences.

Georgie Lou’s life changed when she saw a documentary about Admiral Richard Byrd at the local theater. Byrd was a Navy pilot and adventurer who had flown over the North and South Poles and across the Atlantic. His exploits captured Georgie Lou’s imagination and she told her parents she too wanted to be a pilot and explore the world. Her mother finally said no: she said flying was too dangerous and Georgie Lou should focus on her writing talent instead.

But Georgie Lou had been raised to be independent. She chose a new nickname for herself, Dickey, in honor of Byrd. She sold an article to the U.S. Air Service Magazine advocating for women pilots, called “Why We Want to Fly.” And she applied to MIT’s aerospace engineering program when she was 16. She was admitted on a full tuition scholarship – one of just seven girls in her class. She initially worked as a nanny for room and board, but soon wanted the freedom of her own apartment and turned to freelance article writing to pay the rent.

But Georgie Lou had been raised to be independent. She chose a new nickname for herself, Dickey, in honor of Byrd. She sold an article to the U.S. Air Service Magazine advocating for women pilots, called “Why We Want to Fly.” And she applied to MIT’s aerospace engineering program when she was 16. She was admitted on a full tuition scholarship – one of just seven girls in her class. She initially worked as a nanny for room and board, but soon wanted the freedom of her own apartment and turned to freelance article writing to pay the rent.

Dickey looked for stories by chatting with people at the Coast Guard base, the Naval shipyard, local airports. She convinced a pilot to take her up in his small plane so she could see an emergency food drop first hand, because “I couldn’t see how any reporter could ask for a better vantage point.” Dickey spent more time on her stories than in the classroom, and she flunked out of MIT after two years. She returned home – sad, embarrassed, and at loose ends – and spent the summer watching local air shows and exchanging typing services for flying lessons. When she was told her nearsightedness would disqualify her from making a living as a pilot, she decided to focus on writing about airplanes instead.

Dickey with her parents, brother, and Tony (WI Historical Society)

Dickey moved in with her grandparents in Florida and wrote press releases for a local air show. When she traveled to Havana for an exhibition, a Cuban pilot died in an accident while performing. Dickey immediately called the New York Times to give them a first-hand account of the incident. An editor at TWA Air asked the Times how it got the story so quickly and then asked Dickey to move to New York to write articles for him.

Dickey loved New York. She was 18, had a full-time job in her chosen field, and was taking a weekly photography class offered by the TWA publicity department. The instructor, Tony Chapelle, had been a Navy photographer in World War I. He taught his students that in war, it is the photograph that proves what you saw actually happened. Dickey and Tony fell in love and after they got married in October 1940, Dickey quit her job at TWA to try her luck as a freelance photographer and reporter.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Dickey was born Georgette Louise Meyer on March 14, 1919 in Shorewood, Wisconsin, a suburb of Milwaukee.

- Reader’s Digest sent Dickey to cover the Cuban Revolution in 1958. She traveled with rebel leader Fidel Castro, who referred to Dickey as “the polite little American with all that tiger blood in her veins” After Castro became a dictator himself, Dickey’s disillusionment led her to the anti-Castro movement.

- In 1961, Dickey wrote an autobiography that she initially called The Trouble I’ve Asked For. She changed its title to What’s A Woman Doing Here? – a homage to the question she was asked the most during her war correspondent career.

- Dickey’s first trip to Vietnam was in 1961, on assignment from Reader’s Digest to report on U.S. advisors working with local soldiers in Vietnam and Laos. The work she did there was honored when she became the second woman ever to win the Overseas Press Club of America’s George Polk Memorial Award. The Polk Award is the highest award for bravery and courage given to war correspondents. The Press Club emphasized that she had been on 17 military operations in Vietnam – more than any other American, and that “the importance of the pictures she took in Vietnam lies in the fact that they were made where nobody goes—BEYOND the telegraph lines and jeepible roads.”

- In 1962, while Dickey was embedded with Marine helicopter units, three Marines she was with told her that she had been embedded with their fathers in Iwo Jima and Okinawa 20 years earlier. She wrote later “With a shock I realized I was now covering my second generation of combat Marines—covering them, again, on embattled ground half a world away from home.” Her work became the cover story in the November 1962 issue of National Geographic.

- In 1963, Dickey was awarded the National Press Photographers Association’s Photo of the Year. Her photo of a Marine advisor with South Vietnamese soldiers was the first confirmation that U.S. advisors were actively engaging in combat operations – which the U.S. had denied.

- Dickey didn’t engage in the politics around the wars she covered. She just wanted to report what she witnessed. As the Vietnam War became more unpopular it was harder to find work and Dickey worked for less than the men charged to get the assignments. She returned to Vietnam for the third time in 1964 on assignment from National Geographic to cover how U.S. advisors were working with the Vietnamese navy.

- Dickey spent time in the Dominican Republic in 1965 reporting on the U.S. occupation.

- When Dickey was on assignment for monthly magazines like National Geographic, her stories often were “old news” by the time they were published. In 1965, after a few times of being the first reporter to file a story but getting scooped, she started accepting assignments from the weekly National Observer, which sent her to Vietnam to report on the Seventh Marines’ Operation Black Ferret, a search and destroy mission. It was to be her fourth and final trip there.

- The Marine Corps League created the Dickey Chapelle Award in 1967. The Award recognizes women who have made significant contributions to the morale, well-being and welfare of the U.S. Marine Corps.

- Dickey was made an honorary Marine in 2017 at the United States Marine Corps Combat Correspondents Association banquet, following the approval by the Marine Commandant.

- After Dickey died, there were no women war correspondents in Vietnam. A general tried to officially ban women in 1967, but failed, and other women, like Catherine Leroy, followed in Dickey’s footsteps.

Want to Know More?

Chapelle, Dickey. What’s A Woman Doing Here? A Reporter’s Report on Herself (Morrow NY 1962).

Garofolo, John. Dickey Chapelle Under Fire. Photographs by the First Female War Correspondent Killed In Action (WI Historical Society 2015).

Strochlic, Nina. “Inside the Daring Life of a Forgotten Female War Photographer” (National Geographic Aug. 17, 2018).

Edmund, Aiyana. “6 Female Journalists of the World War II Era” (Literary Ladies Guide Jan. 31, 2018).