Brilliant Businesswoman

She followed her childhood dream of becoming a journalist and started her career by covering the farm industry. Before long, she became passionate about the food cooked by women on farms across America. After a battle with throat cancer, she accepted the fact that television or radio wasn’t in her future and focused on her writing. She even obtained a pilot’s license so she could travel from town to town in search of stories about regional cooking. Along the way, she invented the idea of American cuisine and became America’s first food journalist. Fly back to 1960 and meet Clementine Paddleford …

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

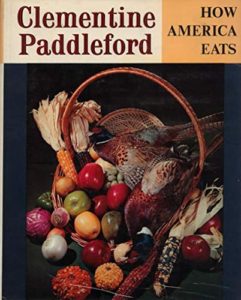

Clementine Paddleford walked past Scribner’s Bookstore and stopped in her tracks. It was December, 1960 and she was walking down Fifth Avenue in New York City. She turned around to get a better look at the window display — right in front of her was a copy of her new book, How America Eats. She was thrilled!

In Clementine’s opinion, the book represented the best articles she had written during her career. She spent over two years methodically going through 12 years worth of her weekly column, How America Eats. She arranged the book geographically and described each region in detail — local recipes, ingredients, traditions, and history.

Clementine got the idea for her weekly column, How America Eats, back in 1947. And it became her most significant work as a writer. She traveled around the country and reported what was being served in American homes. She usually stayed in a destination for one week, interviewed a person in the community, and focused on her specialty in the kitchen. She also highlighted the history behind a recipe and regional variations.

Through How America Eats, Clementine used food to tell the story of America. She introduced the idea of American cuisine — food tied to our melting pot culture of many traditions coming together. She highlighted the fact that each region in America has its own traditions. And she documented how immigrants influenced cooking throughout America, adapting recipes from the old country to a new home.

Clementine also featured famous restaurants in How America Eats. She wanted readers to feel like they were a special treat. She gave the history of the restaurant, revealed secret recipes, and provided readers with a vicarious experience (since they may never visit the restaurant).

Clementine also featured famous restaurants in How America Eats. She wanted readers to feel like they were a special treat. She gave the history of the restaurant, revealed secret recipes, and provided readers with a vicarious experience (since they may never visit the restaurant).

Despite her success, Clementine never forgot her goal — to help the home cook. She sought out unglamorous food that tasted good, was easy to make, and had relatively inexpensive ingredients. She published recipes that we would consider comfort food today. And she wanted to make cooking fun and mealtimes engaging.

Clementine started writing about food when America had few “food traditions.” Food was labeled by its origins, such as Italian or French, and the American influence was ignored. Clementine’s work created “American Cuisine” and changed both the food and journalism industry forever.

The Power of the Wand

Clementine was a pioneer in journalism — she invented the genre of food writing. During the early 1900s, cooking was considered a scientific topic and articles about it were primarily educational and rather dry. Clementine infused passion into the topic. She believed with that food was meant to be an “experience” and not just “sustenance.” As a result, she paved the way for today’s multi-million food industry, including the Food Network, cutting-edge restaurants, and celebrity chefs.

Over the last 50 years, many women have continued Clementine’s legacy — her interest in regional American cuisine, passion for good food, and dedication to the home cook. Today, teen girls like Eliana de Las Casas and Haile Thomas have followed their dreams in the culinary world. Eliana was the 2016 Chopped Teen Grand Champion, then went on to start a spice company and publish a cookbook. Haile Thomas was inspired to cook healthier food when her father was diagnosed with diabetes (she was 7 years old at the time). A few years later, she started a YouTube video series called Kids Can Cook. She also founded The HAPPY Organization, which “promotes youth empowerment through holistic education.”

Her Yellow Brick Road

When the Great Depression started, Clementine was already a well-respected editor in the world of farm publications. But the farm industry was struggling and she needed some job security. So she thought about what people needed, regardless of their hardship or circumstances in life. She came up with food and shoes. And she didn’t want to write about shoes. So she went on a quest to write about food.

Clementine with her cat (Kansas Historical Society)

Clementine got her chance to start writing about food when she became the household editor at the Christian Herald in 1930. Clementine began to experiment with articles about food itself. Her goal was to “involve real home cooks in the world of food journalism.” And she worked on developing her voice — she wrote with enthusiasm, used mouthwatering descriptions of food, and was meticulous in her research.

Then, Clementine was diagnosed with cancer. At age 33, she went to the doctor because of her throat hurt constantly and her voice was hoarse all the time. And she found out she had a tumor. The doctor gave her the choice of two procedures — one that has a higher success rate but would leave her without a voice; and one that was more risky but would preserve her ability to talk. She chose the more risky one.

Clementine had part of her larynx and vocal cords removed, with a tracheal tube placed to allow her to breathe and talk. She splurged on a sterling silver tracheal tube, which was held in place with a black ribbon. It became part of her look. Clementine had to learn how to talk again, pushing a button on her tracheal tube and forcing air out to speak. Her voice was monotone, thin and raspy. So, she also worked on communicating with her eyes and body language.

In 1936, Clementine’s hard work paid off. She finally landed her dream job. She was offered a job at the New York Herald Tribune as its Food Markets Editor. And she took it. She reported on food that people around America cooked and ate everyday at home. She also published recipes — since the New York Herald Tribune had a test kitchen, she could try recipes she gathered on her travels. Clementine spent 30 years at the New York Herald Tribune (1936-1966).

In 1936, Clementine’s hard work paid off. She finally landed her dream job. She was offered a job at the New York Herald Tribune as its Food Markets Editor. And she took it. She reported on food that people around America cooked and ate everyday at home. She also published recipes — since the New York Herald Tribune had a test kitchen, she could try recipes she gathered on her travels. Clementine spent 30 years at the New York Herald Tribune (1936-1966).

Shortly after taking the job at the New York Herald Tribune, she started writing for This Week magazine. It was a supplement in Sunday newspapers across America. As a result, her readership skyrocketed — before long, her articles reached 13 million households. In fact, Clementine balanced two full-time jobs for most of her career. She put in extremely long hours and did whatever it took to get a story.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Food traditions were a big part of Clementine’s childhood. Her mother studied home economics at Kansas State College and was an avid gardener. She taught Clementine what it took to put food on the table. Clementine understood how much work went into growing food, since she lived on a farm until she was about 10 years old. Then, her father purchased a grocery store in Manhattan and she learned about the retail side of things. As a result, Clementine had a deep understanding of the food and farming industries.

Clementine knew she wanted to be a journalist at an early age. Sometimes she would wake up early and go to the train station, to see if she could get a scoop on any of the town residents. She wrote for her high school newspaper, was editor of her college newspaper, and then majored in industrial journalism in college.

Clementine in high school (Manhattan High School Alumni Association)

After graduation, Clementine moved to New York (since it was the center of the publishing world). She took some graduate classes at NYU and did some freelance jobs for newspapers such as the New York Sun. But they were tough years. Clementine was unhappy, lonely, and unemployed.

In 1923, Clementine visited some friends in Chicago. And she decided to stay. She was offered a position at the Agricultural News Service. It wasn’t her dream job, but it was a good place start. It was a topic she knew and she was getting experience. She learned how to dig for facts. She got practice interviewing sources. And her hard work paid off.

Clementine moved back to New York City to take a job as the household editor for Farm & Fireside (later it was known as the National Farm Magazine). She wrote stories on topics helpful for farm women. Eventually, her goal was to interact with one farm woman every single day. She traveled around the country and interviewed farm wives. Then, she began to receive mail from women around country. And the insight she received was invaluable.

While at Farm & Fireside, Clementine gained a deep understanding of the working class American woman of her era. She developed a respect for the challenges of their lives and began to understand their needs. And she relied on that knowledge for the next chapter of her career.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Clementine grew up in Kansas. Her family moved to Manhattan to provide a better education and more opportunities for Clementine and her older brother, Glenn.

- Clementine graduated from Kansas State Agricultural College in 1921 with a degree in industrial journalism.

- Clementine married college boyfriend in secret but never lived in the same City with him. They divorced 9 years later.

- After her college friend (who was a single parent) died of cancer, Clementine adopted her daughter and raised her. She and Claire grew very close over the years.

- Clementine got her pilots license so she could more easily travel around America and report on regional cuisine.

- Clementine also traveled internationally for her job, including Russia, Hong Kong, Mexico and England. In 1953, she reported on the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

- She covered the fun side of many famous events in America, including the food that was served to Winston Churchill when he visited Truman in Missouri.

- In July 1960 at age 62 Clementine decided to do a story about making meals aboard a nuclear submarine. She boarded the USS Ship-Jack, the fastest nuclear sub at the time. It took her about one year to get all the necessary approvals to do the story.

- Clementine died on November 13, 1967.

- In her will, Clementine bequeathed all her professional papers to her alma mater, Kansas State University — 1900 cookbooks, 700 restaurant menus, awards, notes for all her articles, and other professional items (274 boxes worth of stuff). No one looked at it for 34 years.

- The Times Herald folded in 1966 and Clementine’s book was out of print by 1969. She was forgotten for many years.

Want to Know More?

Alexander, Kelly and Cynthia Harris. Hometown Appetites: The Story of Clementine Paddleford, the Forgotten Food Writer Who Chronicled How America Ate. New York: Penguin Random House, 2008.

Paddleford, Clementine. How America Eats. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1960.

“Clementine Paddleford is Dead; Food Editor of the Herald Tribune.” The New York Times, November 14, 1967 (https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1967/11/14/90417700.html)

“Clementine Paddleford.” Manhattan High School Alumni Association (https://www.lib.k-state.edu/depts/sc_rev/exhibits/paddleford/writes.php).

“Clementine Paddleford.” Kansapedia. Kansas Historical Society (https://www.kshs.org/kansapedia/clementine-paddleford/12162)