Passionate Patriot

She grew up in a house filled with books and took her love for learning with her to Wilberforce College, where she earned a spot in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps’s first officer candidate school. As she rose through the ranks to become the first Black woman to command an Army unit, she faced discrimination at every turn, but kept moving forward. She led her battalion in delivering over 17 million pieces of backlogged mail, in record time, to our World War II troops stationed in Europe. This morale saving mission lifted our soldiers at the front when they needed it most. Travel back in time to a 1945 airplane hangar in England and meet Charity Adams Earley...

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

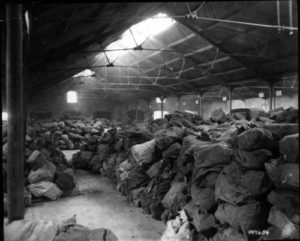

Charity Adams was stunned as she stood on front of an airplane hangar filled with haphazard piles and piles of undelivered Christmas packages. Then he learned there were five more airplane hangars just like it. It was January 28, 1945 and America was in the middle of World War II. Charity was in command of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion in Birmingham, England (the “Six Triple Eight”). It was their job to deliver over 17 million pieces of backlogged mail to American soldiers serving in Europe.

Airplane hangar filled with mail in England (National Archives)

The Six Triple Eight was the first and only battalion of Black WACs to be stationed overseas, over 850 women in total. And Charity worried they were being set up to fail. She realized, however, that England was the perfect place to prove that Black women were up to the task. Charity felt liberated in London. Her minority status seemed to disappear among the people of all colors, races and religions that walked the streets. In fact, most of the discrimination she experienced while in England was from other Americans.

There were 7 million American soldiers stationed in the European theater who were eagerly awaiting their mail. So Charity got to work. She organized the Six Triple Eight into 4 companies (A-D), each with specific duties. Then, she split each company into three groups that worked 8 hours shifts each. Before long, they were sorting mail 24 hours per day, 7 days per week.

There were 7 million American soldiers stationed in the European theater who were eagerly awaiting their mail. So Charity got to work. She organized the Six Triple Eight into 4 companies (A-D), each with specific duties. Then, she split each company into three groups that worked 8 hours shifts each. Before long, they were sorting mail 24 hours per day, 7 days per week.

First, the women had to verify the correct recipient of each letter. Which wasn’t always easy, especially if the label didn’t include a soldier’s identification number. For example, there were more than 7,500 “Robert Smiths” serving in Europe at the same time. Then, the women needed to figure out where that soldier was located. So they referred to the Army’s system of index cards for each soldier. Hopefully. If a soldier didn’t complete a change of address form when changing locations, however, all bets were off. In that case, the women had to become investigators.

6888th sorting mail with civilians in France (National Archives)

The Six Triple Eight processed about 65,000 pieces of mail every single day. And the longer the women worked on the job, the more they understood its importance. Their mission wasn’t glamorous. But it was critical to the morale of the troops. In fact, The Six Triple Eight’s unofficial motto was “No mail, low morale.” And they became determined to become the fastest and most reliable mail directory in Europe. Charity was told to clear all the backlogged mail in 6 months. The Six Triple Eight did it in half that time!

After the Six Triple Eight cleared the backlog of mail in England, they were stationed in France to do the same thing. After Germany’s surrender in May 1945, they were in Rouen to clear another postal jam. Then, they moved to Paris in the fall of 1945. Their duties became more difficult after the War officially ended — soldiers were constantly on the move and preparing to return home. But they persevered and delivered mail to soldiers until the day they were ordered home to the US in December 1945.

The Power of the Wand

Charity led the largest unit of Black women in World War II. She was also the first African American commanding officer in WAC to serve on a tour of duty overseas during WW2. And she retired as the highest ranking Black female officer in the WAC (Lieutenant Colonel). Charity helped to break down the prejudices she saw in the Army. And then, she spent the rest of her life advocating for racial equality in her Ohio community.

Black women are still following Charity’s example and breaking glass ceilings in the military. This semester, Sydney Barber was chosen as the first Black woman to serve as the brigade commander at the US Naval Academy. The position is similar to president in student government. Sydney graduates from the Naval Academy this spring. Charity would have been proud of her!

Her Yellow Brick Road

Charity arrived at Fort Des Moines, Iowa in July, 1942, as a member of the very first WAAC officer candidate school. She was one of 39 Black women officer candidates. Back then the Army was officially segregated — she served in a segregated platoon and lived in segregated housing. Sometimes, she felt isolated as a result of her race. For example, white officer candidates were called by their names, while Black officer candidates were merely called “the colored girls.”

Charity graduated on August 29, 1942 and was assigned to the Black platoon of the Third Company, Third Training Regiment. She was stationed in Des Moines for 2 years and trained the new Black officer recruits. She took her job seriously and trained them well. Then, she began to move up the ranks — from Training Officer to Company Commander to Training Supervisor to Major.

Charity graduated on August 29, 1942 and was assigned to the Black platoon of the Third Company, Third Training Regiment. She was stationed in Des Moines for 2 years and trained the new Black officer recruits. She took her job seriously and trained them well. Then, she began to move up the ranks — from Training Officer to Company Commander to Training Supervisor to Major.

Regardless of how many promotions Charity received, however, she still experienced discrimination. People didn’t believe that she was a Major in the WAC and asked to look at her credentials over and over. Some thought they were forged. Other people refused to accept her in the officer clubs and dining halls. In fact, she was denied a seat in the dining car when she traveled home by train while on leave.

Charity in WAC (Library of Congress)

Then, Charity was given a new assignment at the end of 1944. She became the commanding officer of the first WAC unit of Black women and would be stationed overseas. She received her orders in a sealed envelope and told to not open until their flight took off. She didn’t know where she was going until they were on the a C-54 cargo plane over the Atlantic. She finally ripped open her envelope and found out she would be stationed somewhere in England.

Brains, Heart & Courage

While Charity grew up, her parents placed an emphasis on education and her house always filled with books. Her dad was a pastor and scholar, and was fluent in Greek and Hebrew. Her mom was a schoolteacher and taught Charity how to read at an early age.

Charity’s family experienced racial discrimination in all aspects of life. Her parents led by example and quietly stood up to the discrimination in Jim Crow South. For example, legend says that her father cancelled an insurance policy when the traveling salesman refused to refer to Charity with respect and call her “Miss.” He eventually became president of the NAACP chapter in Columbia. Once, her family home was surrounded by the KKK as a warning to her father. They wanted him to quit the NAACP. But he stood his ground.

Charity was really smart — she skipped two grades in elementary school and graduated valedictorian from Booker T. Washington High School. Then she received a scholarship to attend Wilburforce University in Ohio, one of the best African American colleges at the time. She majored in mathematics, Latin, and physics. She also took classes in history and education.

Charity was really smart — she skipped two grades in elementary school and graduated valedictorian from Booker T. Washington High School. Then she received a scholarship to attend Wilburforce University in Ohio, one of the best African American colleges at the time. She majored in mathematics, Latin, and physics. She also took classes in history and education.

In 1942, the Army announced that it would accept 40 Black women into its Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps. And it was up to the Black leaders of America to recommend candidates. The dean of Wilberforce recommended Charity for the first class of the WAAC officer candidate school.

Charity applied in June 1942. She didn’t receive any response, however, so she went on with her life and forgot all about it. Then, her aunt frantically waved her down in the Knoxville train station while she was traveling back to Ohio State University for graduate school. Charity needed to call home — the Army wanted her.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Charity Adams was born on December 5, 1918 in Kittrell, North Carolina. She grew up in Columbia, South Carolina as the oldest of 4 children.

- After college, Charity was an elementary school teacher, while also pursuing a masters degree in vocational psychology from Ohio State University. Then America entered World War II. Charity served throughout the War and was relieved from duty in March 1946.

- The National Council of Negro Women named her Woman of the Year in 1946.

- Charity returned to Ohio State University to complete her masters degree after the War ended. Then she worked for the Veterans Administration. She went on to serve as Dean of Students at Georgia State College.

- Charity married Stanley A. Earley Jr. on August 24, 1949 and moved to Zurich, Switzerland while he finished his medical training. They had 2 children, a son and daughter.

- When they returned to Ohio, Charity became active in charity and community work. Over her lifetime, she was involved in the following organizations: United Negro College Fund, United Way, Urban League, YWCA, Dayton Power and Light, Dayton Metro Housing Authority, Dayton Opera Company, American Red Cross and Sinclair Community College.

- Charity helped to found the Black Leadership Development Program in Dayton, Ohio in 1982. Its purpose was to educate and train African Americans to be leaders in their communities.

- The National Postal Museum honored Charity for her work during World War II. She also received a number of honors over the years: Ohio Women’s Hall of Fame, Ohio Veterans Hall of Fame, South Carolina Black Hall of Fame, Ohio State Senate, among others.

- Charity died at age 83 on January 13, 2002. Her family requested an honor guard for her funeral but the Army aid no. Then an Air Force general learned of her passing and offered their own honor guards. The Army reversed its decision and two honor guards were at Charity’s funeral — one from the Army and one from the Air Force.

- Finally, the Army awarded the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion a “Meritorious Unit Commendation” in 2019 for its outstanding service in World War II.

Want to Know More?

Brown Fisher, Christina. “The Black Female Battalion That Stood Up to a White Male Army.” New York Times Magazine, June 17, 2020 (updated Sept 2, 2020).

Creamer, Maureen. “Earley, Charity Adams” in Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia (Brooklyn, N.Y.: Carlson Publishing Inc., 1993), pp. 375-377.

Earley, Charity Adams. One Woman’s Army: A Black Officer Remembers the WAC. College Station, Tx.: Texas A & M University Press, 1989.

Hymel, Kevin. 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion. The Army Historical Foundation (https://armyhistory.org/6888th-central-postal-directory-battalion/)

Weston, Zack. Biographical sketch of Charity Edna Adams Earley. South Carolina Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia, S.C.

Women of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion (https://www.womenofthe6888th.org)

Charity Adams Earley’s papers are located at the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/mm2003084973/)