Audacious Adventurer

Her dream to be a pilot hit a roadblock when no American flight school would train her. So she worked two jobs, learned a new language, and headed to France to become the first Black woman in the world to earn an International Pilot’s License. She returned home to thrill audiences with her skills. Climb into the cockpit of a 1925 biplane and meet Bessie Coleman…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

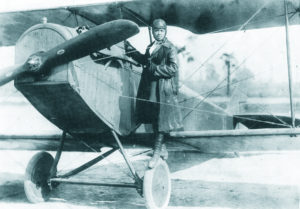

Bessie and a “Jenny” Plane (Cradle of Aviation Museum)

Bessie Coleman walked around her airplane to do her standard equipment check. It was a clear day in Houston, Texas and Bessie was about to entertain a large crowd with a flying exhibition. People had asked if she was nervous to be back in the pilot’s seat. She wasn’t, but she understood why they were wondering.

Bessie had recently been hospitalized for three months after a terrible accident. She had saved $400 to buy a used plane and it stalled at 300 feet and crashed in an air show the first time she flew it. Bessie broke her leg and three ribs, cut her face in several places, and bruised her internal organs. While her body was broken, her spirit was not, as evidenced by the telegram she sent to reporters from her hospital bed: “tell them all that as soon as I can walk I’m going to fly!” When Bessie was strong enough to leave the hospital, she went home to Chicago to prepare for a series of exhibition flights and lectures in Texas.

Bessie had been waiting a long time to be back in the air, and her return was made even sweeter as she watched everyone walk in through the same gate. Like most other Texas venues, there were two entrance gates and two bleacher sections: one for Black spectators and the other for white ones. But Bessie told the sponsors that she would not fly in their exhibition unless everyone could use the same entrance. Bessie attracted big crowds of both races, and since the sponsors didn’t want to lose ticket sales, they agreed and scheduled the exhibition for Juneteenth (June 19) 1925.

Bessie had been waiting a long time to be back in the air, and her return was made even sweeter as she watched everyone walk in through the same gate. Like most other Texas venues, there were two entrance gates and two bleacher sections: one for Black spectators and the other for white ones. But Bessie told the sponsors that she would not fly in their exhibition unless everyone could use the same entrance. Bessie attracted big crowds of both races, and since the sponsors didn’t want to lose ticket sales, they agreed and scheduled the exhibition for Juneteenth (June 19) 1925.

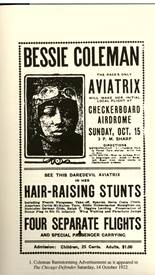

As the crowd settled into its seats, Bessie climbed into the open cockpit to review her final checklist for takeoff. While she worked, she thought back to her first show a few years earlier, on a sunny Labor Day in New York. Over 2000 people had watched Bessie become the first Black and Native American woman to perform a public flight in the United States. Bessie had to borrow a plane for the show and the owner said no stunts, so she simply took off, turned around, and landed. The crowd was still thrilled, especially when Bessie offered rides to lucky audience members after her flight.

As the crowd settled into its seats, Bessie climbed into the open cockpit to review her final checklist for takeoff. While she worked, she thought back to her first show a few years earlier, on a sunny Labor Day in New York. Over 2000 people had watched Bessie become the first Black and Native American woman to perform a public flight in the United States. Bessie had to borrow a plane for the show and the owner said no stunts, so she simply took off, turned around, and landed. The crowd was still thrilled, especially when Bessie offered rides to lucky audience members after her flight.

The Chicago Defender newspaper coverage of her flight made her a media sensation. Soon papers all over the country were writing about “Brave Bessie” and “Queen Bess.” Billboard Magazine noted that “[p]robably more people of color went up that day than had ever flown since planes were invented.”

Bessie started touring the country to fly in exhibitions, which was the main way she could make a living flying because businesses weren’t willing to hire a Black woman as a pilot. Soon Bessie’s audiences wanted a more thrilling show than just take off and touch down, so she needed more training tricks that sold tickets. She applied to all of the United States flight schools for more training and was rejected. She returned to France, where she had first gotten her pilot’s license and took lessons from a World War I flying ace.

Bessie started touring the country to fly in exhibitions, which was the main way she could make a living flying because businesses weren’t willing to hire a Black woman as a pilot. Soon Bessie’s audiences wanted a more thrilling show than just take off and touch down, so she needed more training tricks that sold tickets. She applied to all of the United States flight schools for more training and was rejected. She returned to France, where she had first gotten her pilot’s license and took lessons from a World War I flying ace.

Bessie brought her thoughts back to the present as she finished her checklist and waved to the Houston crowd. She accelerated for take off, confident that her audience didn’t care about her gender or color so long as she could fly. Bessie stalled, dove, barrel rolled, did figure eights, and looped the loop through the Houston sky. She took audience members up for rides. The Houston Informer reported that it was “the first time the colored public of the South have been given the opportunity to fly.”

The Power of the Wand

Bessie’s bravery and spirit live on in young women pilots today. Kimberly Anyadike was just 15 years old when, in 2009, she became the youngest Black woman to fly across the country. Kimberly piloted a Cessna airplane from Los Angeles, CA to Newport News, VA and then back to Los Angeles. Her trip took 13 days and she made several stops along the way to have her plane signed by Tuskagee Airmen.

Kimberly grew up in Compton, CA. She got her start as a pilot by attending an after-school aviation program for disadvantaged youths sponsored by Tomorrow’s Aeronautical Museum. Kimberly went on to graduate from UCLA with a degree in Physiological Science.

Her Yellow Brick Road

When World War I ended, Bessie’s brother John returned to their home in Chicago and shared his experiences as an American soldier overseas. Bessie was hungry to experience the world herself, and was particularly inspired by John’s stories of the brave French women pilots who flew missions for the war effort. Although Bessie had been interested in airplanes and flight since her school days. John teased her that she could never fly like the French women.

Bessie wasn’t discouraged, even though there were no Black pilots – men or women – in the United States. She was simply thrilled to hear that there were women somewhere in the world flying airplanes. Bessie applied to several flight schools around the United States, but they all rejected her because they didn’t train minorities or women.

Bessie wasn’t discouraged, even though there were no Black pilots – men or women – in the United States. She was simply thrilled to hear that there were women somewhere in the world flying airplanes. Bessie applied to several flight schools around the United States, but they all rejected her because they didn’t train minorities or women.

Bessie realized she would have to go to Europe to become a pilot. She pitched her story to Robert Abbott, owner of the Chicago Defender, which was the most influential Black newspaper in the country. She persuaded him that stories about a Black woman pilot would help sell newspapers. Robert suggested that Bessie apply to flight school in France because he believed it was the world’s most racially progressive nation. He offered to give her the reference she needed to be admitted once she saved enough money for tuition and learned French.

Bessie enrolled in a Berlitz French language course and worked two jobs as a manicurist and a chili parlor manager. When she started applying to French flight schools, the first one rejected her because she was a woman. The second school, the Caudron Brothers’ School of Aviation in Le Crotoy, said yes. Bessie left for France and her new career on November 20, 1920, just 6 days before her 28th birthday.

Bessie in 1922 (Smithsonian Museum of Air & Space)

Bessie was the only Black student and only woman in her class. The only room she could afford was 9 miles away from the airfield and she had to walk there and back each day. The students learned in 27 foot biplanes made of wood, wire, steel, aluminum, cloth and pressed cardboard. The planes had no steering wheels or brakes.

These training planes had front and rear cockpits with duplicate controls. A baseball bat sized stick moved the nose up and down, and a foot controlled rudder turned the plane left and right. The students rode in the rear and watched and copied the instructor’s actions. On landing, the students learned to lower the metal tail into to the ground to drag the plane to a stop. Accidents were frequent and sometimes serious. Bessie witnessed one of her fellow students die in a crash.

Bessie’s Pilot License (bessiecoleman.org)

Bessie completed the ten month flying course in seven months and took her licensing exam on June 15, 1921. To pass, she had to fly through a 3.1 mile closed course two times, climb to 164 feet, do a figure eight, land within 164 feet of a marked point, and turn off her engine before her wheels touched the ground. When she landed, she became the first Black woman in the world to earn an International Pilot License.

Bessie spent the rest of the summer flying in air shows around Europe. She returned to the United States in September 1921 with two goals in mind: to make a living flying and establish a flight school open to women and all races. But first, she was to appear in an exhibition in New York sponsored by Robert Abbott and the Defender.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Bessie grew up in a sharecropper family in Texas. Her first home was a one room cabin and every member of the family worked in the cotton fields. Four of Bessie’s 12 siblings died very young. The surviving Coleman kids attended school whenever they could be spared from work. Bessie started school when she was 6, walking 4 miles to the one room school Black children were allowed to attend.

The Colemans eventually bought a 3 room house in a neighboring town, still earning a living in the cotton fields. Cotton pickers were paid by the pound. Bessie used her math and record keeping skills to make sure her family wasn’t being cheated by storekeepers, who often took advantage of pickers’ lack of education.

The Colemans eventually bought a 3 room house in a neighboring town, still earning a living in the cotton fields. Cotton pickers were paid by the pound. Bessie used her math and record keeping skills to make sure her family wasn’t being cheated by storekeepers, who often took advantage of pickers’ lack of education.

A railroad track through town separated the white and Black areas. Bessie’s dad, who was part American Indian, grew tired of dealing with the racism and moved to an Indian reservation in Oklahoma when Bessie was 9. Bessie’s older brothers left soon afterward, moving north to look for better jobs and less discrimination. Her mom found a job working as a housekeeper for a white family, leaving Bessie to care for her three younger sisters.

Bessie was able to start school again once her younger sisters were old enough to stay alone. She completed all 8 grades at the Missionary Baptist Church School between the ages of 12-16. She borrowed books from the traveling library to study for the high school graduation exam and worked as a laundress to save money for college. She attended college in Oklahoma but could only afford one semester before she had to return home. She decided to join her brothers in Chicago. Her first job there was doing men’s nails at a salon on State Street, where she won an award for best and fastest manicurist in Chicago.

Bessie was able to start school again once her younger sisters were old enough to stay alone. She completed all 8 grades at the Missionary Baptist Church School between the ages of 12-16. She borrowed books from the traveling library to study for the high school graduation exam and worked as a laundress to save money for college. She attended college in Oklahoma but could only afford one semester before she had to return home. She decided to join her brothers in Chicago. Her first job there was doing men’s nails at a salon on State Street, where she won an award for best and fastest manicurist in Chicago.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Bessie was born on November 26, 1892 in Atlanta, Texas.

- After her 1925 Houston show, Bessie kept touring throughout the south. At some shows, she would bring another pilot along so she could jump out of the cockpit and parachute down. Crowds loved it. When she learned an Orlando venue was whites only, she refused to jump until the sponsors allowed Black people to attend.

- Bessie’s popularity enabled her to demand more and more integration at the venues where she flew. She starting refusing to perform unless seating was integrated so Black and white spectators could sit with each other.

- Bessie’s eight year old nephew was inspired to learn to fly when he watched one his Aunt Bessie’s Chicago airshow. He became one of the Tuskegee Airmen, who were the first Black pilots in the U.S. Army.

- Bessie’s ultimate goal was to start a flight school open to anyone who wanted to learn to fly, but she needed her own plane to do so. She saved money to buy a plane with her flying exhibitions and profits from a beauty salon she opened in Orlando.

- Bessie booked an air show in Jacksonville, Florida for her debut in her new plane. William Willis, a pilot and mechanic, delivered the plane to her from Texas and ran into a few mechanical problems along the way.

- On April 30, 1926, William and Bessie did some maintenance on the plane and then took it up for a test flight, with Bessie in the rear cockpit so she could scout potential landing spots for a parachute jump. Bessie undid her seat belt to lean over the edge of plane so she could see the ground and an unsecured wrench jammed the controls, causing the plane to suddenly accelerate, nose dive, and flip upside down. Bessie fell out and died when she hit the ground. William was unable to regain control of the plane and it crashed, killing him as well.

- Ten thousand people came to Bessie’s funeral and Bessie Coleman Flying Clubs started around the country. On Labor Day 1931, the Bessie Coleman Aero Club of Los Angeles sponsored the first all Black Air Show, attracting 15,000 spectators.

- In 1977, Black women pilots founded the Bessie Coleman Aviators Club, which celebrated her legacy and flew over her grave every year.

- The U.S. Postal Service honored Bessie with a stamp as part of its Black Heritage Stamp Series in 1995.

Want to Know More?

Alexander, Carol, Bessie Coleman: Trailblazing Pilot (Scholastic 2016).

Chicago Defender, “Aviatrix Must Sign Away Life to Learn Trade” (Oct. 8, 1921).

Bix, Amy, “Bessie Coleman: Race and Gender Realities Behind Aviation Dreams” (2005). History Publications. 11.

Small, Kathleen, Bessie Coleman: First Female African American and Native American Pilot (Cavendish Square Publishing 2018).

PBS American Experience. “Bessie Coleman”