Amazing Artist

She moved from Florida to New York City with only $25 to her name to pursue her dream of being a sculptor. After being rejected for art training because of her race, gender, or both, she found a home at an art school in the midst of the Harlem Renaissance. Her art quickly started speaking for itself, and led to a commission to create a sculpture celebrating the musical contribution of African Americans for the World’s Fair. Walk into a 1939 art studio for a first look at The Harp – which would soon become one of the most famous sculptures in the world – and meet Augusta Savage…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

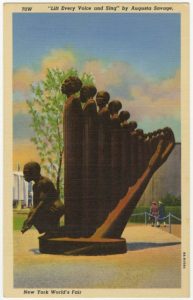

Augusta Savage worked furiously in her studio. She was behind schedule on her sculpture for the 1939 New York World’s Fair. It was the most complicated piece she had ever designed — it would become the most famous of her career as well.

In 1937, Augusta was commissioned by the New York State World’s Fair Commission to create a sculpture that celebrated the musical contributions of African Americans. She was the only black woman who was given a commission in connection with the Fair. And she was paid $360 for her efforts (about $6,600 today).

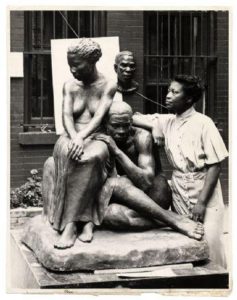

August works on “The Harp.” New York Public Library

Augusta called her sculpture The Harp — her goal was to symbolize African American spirituals and hymns. She was inspired by James Weldon Johnson’s 1900 poem entitled Lift Every Voice and Sing (at the time, it was considered the “Negro national anthem”).

Augusta created a 16 foot masterpiece. It was a harp made out of African American children — 12 African American singers were the strings of the harp; a kneeling man holding music was at the base of the harp; the arm and hand of God was the frame of the harp. The people were lined up in order of height, like the strings of a harp.

The Harp was cast in plaster and then painted to resemble black basalt, since it would have been too expensive to cast the sculpture in bronze. It was a technique that Augusta had used many times before — she simply didn’t have the money to cast any of her sculptures in metal.

Postcard of “The Harp” from the 1939 World’s Fair. New York Public Library

The grand opening of the Fair was on April 30, 1939 — the 150th anniversary of Washington’s inauguration in New York City. The Fair’s theme was “Building the World of Tomorrow.” The fairgrounds were in Flushing Meadows, Queens. Over 44 million people attended the fair over two seasons (April – October).

The Harp was exhibited in the plaza of the Contemporary Arts building. Over 5 million visitors saw her sculpture. And it was well-received. People talked about it. People drew it. People photographed it. People purchased replicas and postcards of it as souvenirs.

But no one had the room to store The Harp after the fair closed on October 27, 1940. So it was destroyed along with most of the other art commissioned for the World’s Fair. Bulldozers leveled it as part cleaning up the fairgrounds.

Augusta took a two year leave of absence from the Harlem Community Art Center to design and sculpt The Harp. Unfortunately, the position was filled in the meantime and she was out of a job when she completed the sculpture. Little did she know The Harp would be her last major commission.

The Power of the Wand

Augusta was an artist, activist, and educator during the Harlem Renaissance. She overcame poverty and racism. She persevered in her dream to become an artist. Then, she devoted herself to mentoring the next generation of black artists. In fact, many of her students went on to become famous artists themselves. And she considered their success to be her greatest accomplishment. Augusta has been an example and inspiration to countless women in the art world ever since.

Professional artist Dimitra Milan was so devoted to her career that she graduated from high school two years early. She was exposed to art as a young girl, since both of her parents were artists and founded the Milan Art Institute in Arizona. Now, she is an instructor and co-owner of Milan Art Institute. And she regularly donates her paintings to nonprofit organizations that advocate against human trafficking. All at age 20.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Augusta arrived in New York City with $4.60 in her pocket in 1921. She had hoped to study under sculptor Solon Borglum, but he refused to teach a woman. So Augusta attended Copper Union, an art school that didn’t charge a tuition. She worked hard, completing a four year course in three years. Then, she continued her studies at the New York School of Applied Design for Women.

In 1923, Augusta applied to study at the Fontainebleau School of Fine Arts in France. She was initially offered a scholarship, but then it was rescinded when the school realized she was a Black woman. So Augusta protested. It was a brave act and put her at the forefront of conversations about race in the art world.

“Gamin,” by Augusta Savage. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Augusta arrived in New York City during the Harlem Renaissance. During the 1920s, Harlem was the the Black capital of America — politically, culturally, intellectually and spiritually. African Americans were reclaiming their heritage, documenting the struggle of racism, and expressing the Black experience. And artists were a critical part of the movement. The result was an intense burst of creativity by African Americans in music, art and literature.

The Harlem Renaissance was a period of great change for African Americans. Thousands of Black families fled from the South as part of the Great Migration. And many settled in northern cities, seeking opportunity. In addition, Black men returned from serving their country in World War I. They were treated well in France and wanted the same respect at home. Before long, Harlem was a magnet for African Americans throughout the nation.

Augusta became a leader in the Harlem Renaissance. She became close with other leaders in the movement and was even commissioned to sculpt their portraits (WE du Bois and Marcus Garvey some to mind). In fact, one of her sculptures became synonymous with the Harlem Renaissance — Gamin. It was a life-sized bust of a Black boy with a cap on his head. Some people think the sitter was her nephew, while others think it was a homeless boy. Regardless of who it was, Gamin earned her a scholarship that changed her life.

In 1929, Augusta was awarded the Julius Rosenwald fellowship (her application submission was Gamin). She was off to France! Augusta spent two years in Paris and loved every moment. She had the freedom to experiment and express her art in a way that wouldn’t have been accepted in America. While in France, she focused on sculpting women— African Amazons and dancers in particular. Her work was bold and contemporary, and was exhibited in the Grand Palais.

In 1929, Augusta was awarded the Julius Rosenwald fellowship (her application submission was Gamin). She was off to France! Augusta spent two years in Paris and loved every moment. She had the freedom to experiment and express her art in a way that wouldn’t have been accepted in America. While in France, she focused on sculpting women— African Amazons and dancers in particular. Her work was bold and contemporary, and was exhibited in the Grand Palais.

Then, Augusta returned to New York City when the Great Depression began. Since there was no work, she decided to teach. In 1932, Augusta founded her own studio and art academy, the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts. She offered free classes to black youth and discovered that she loved to introduce children to art.

In 1937, Augusta became the first executive director of the Harlem Community Art Center. It was funded by the Works Progress Administration of the federal government and operated from 1937-1942. The goal was to make art accessible to the community through free exhibits and instruction. In the first year of its operation, over 70,000 people participated in its events and classes. Before long, it became the gathering place for artists of the Harlem Renaissance.

Brains, Heart & Courage

When Augusta was young, her backyard in Green Springs, Florida, was filled with natural clay. And she loved to play in it. She got dirty from head to toe and loved the feel of the clay squishing between her fingers. Before long, she made little animals from the clay. And she was hooked. Sometimes, Augusta skipped school and spent the day sculpting her animals instead.

Augusta’s dad didn’t approve of her favorite pastime — it wasn’t appropriate for a girl to get so messy. He was a minister and wanted her to her read the Bible instead. He didn’t understand Augusta’s passion for sculpture and art. And he smashed all of her sculpted animals. In fact, Augusta hid her creations in her mom’s trunk so that her dad wouldn’t find them.

Augusta with her sculpture “Realization.” Andrew Herman. Federal Art Project, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

When Augusta was 15 years old, the family moved to West Palm Beach. Aiugista was sad because she couldn’t work with clay from their yard anymore (the dirt was too sandy). But then, she found a pottery factory called “Chase Pottery” and begged for some leftover clay. It was her lucky day — the owner gave her three buckets of clay.

Augusta continued making her beloved clay animals. But she also branched out and experimented with other subjects. For example, she made a statue of the Virgin Mary. Augusta’s school principal was impressed with her creations. After graduation, he paid her $1 per day to teach art at the school.

When Augusta was 27 years old, she entered some of her pieces in the West Palm Beach County Fair. And she won! The prize was $25. George Graham Currie, who operated the Fair, was impressed with her work and suggested that she pursue her dream of becoming an artist. It was all the encouragement she needed. Augusta used her $25 prize to get herself up to New York City and start a new life.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Augusta was born on February 29, 1892 (leap year!) in Green Cove Springs, Florida. She was the 7th of 14 children.

- Augusta received two Julius Rosenwald fellowships and one Carnegie Foundation grant.

- Augusta was the first black artist to join the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors.

- Augusta helped to found the Harlem Artists’ Guild.

- Augusta’s bust of WE du Bois and Gamin were both on display at the Harlem Public Library for many years. Now, they are at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

- Augusta was married three times — her husbands were John T Moore, James Savage, and Robert Lincoln Preston. She and Moore had a daughter named Irene.

- Augusta lobbied the federal government’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) to admit African American artists into its Federal Art Program and became an assistant supervisor in the program.

- Her career never recovered the time off she took to sculpt The Harp.

- Augusta founded the Salon of Contemporary Negro Art — it was the first gallery dedicated to the sale and exhibition of African American artists. She opened it on June 8, 1939 and over 500 people attended the opening night. Unfortunately, it closed within 3 months. Augusta’s vision was ahead of its time.

- In 1945, Augusta moved to the Castkill Mountains of western New York. She continued to teach art to children and create her own works for over 15 years. She also wrote children’s stories, but never published any of them.

- In 1962, she moved back to NYC to be with her daughter after her health started to fail.

- Very little of Augusta’s work survives — some people think that she destroyed much of her work when she struggled with depression.

- Augusta died from cancer on March 26, 1962 in New York City.

Want to Know More?

“Augusta Savage,” Smithsonian American Art Museum (https://americanart.si.edu/artist/augusta-savage-4269)

Lift Every Voice and Sing (The Harp), Augusta Savage, 1939 (http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/maai3/community/text4/savagetheharp.pdf)

1939 New York World’s Fair (https://www.1939nyworldsfair.com)

Hayes, Jeffrey. Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman. Jacksonville: Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens, 2018.

Haygood, Wil. I Too Sing America: the Harlem Renaissance at 100. New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2018.

Kirschke, Amy, ed. Women Artists of the Harlem Renaissance. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014.