Audacious Adventurer

She was a Civil War era teenager inspired by the speeches she heard from abolitionists and suffragettes about freedom. She had a heart for adventure, travel and embracing challenges that was stronger than the limits society tried to place on women. She became a famous speaker in her own right by sharing the experiences climbing the world’s mountains with other dreamers. Check out the view from the summit of Mount Huascarán in the Andes Mountains of Peru in 1908 and meet Annie Smith Peck…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Annie Smith Peck stood on the summit of Mount Huascarán in the Andes Mountains of Peru – reveling in the knowledge that no other human had ever seen the view from its top before today, September 2, 1908. While it was summer at home, Annie and her two mountain guides had fought through ice, wind, and snow to complete their climb.

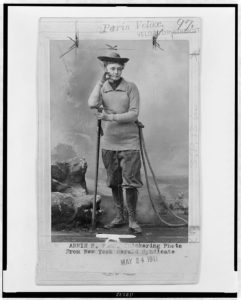

Annie in her Mount Huascarán gear. Her face is completely covered by a face mask for warmth.

This was Annie’s sixth attempt. She had first tried four years earlier to climb what many believed to be the highest peak in South America. One of its main attractions for her was that nobody – man or woman – had ever reached its summit.

Annie had learned a lot from her five failed attempts. When she first tried in1904, she couldn’t afford professional mountain guides. Instead, she recruited companions to accompany her once she arrived in Peru. But since they had little climbing experience, Annie was on her own for strategy. She studied the two peaks of Huascarán and decided to approach the north peak from the east in order to avoid several glacier crevasses on the west. It was the wrong choice. The terrain was steep and covered in deep snow. After climbing only 4000 feet in 4 days, they had to turn back.

Annie made a second attempt from the west. They made more progress this time, but at 15,800 feet, just short of the glacier, there was a difference of opinion between Annie and one of the men about which way to go. The others chose to follow the man, even though Annie was the only experienced climber. His path was impassable and they had to turn back again. While Annie was frustrated, she also concluded that she “had done enough to show that I was not insane in believing that I was personally capable, with proper assistance, of making the ascent of a great mountain.”

Annie and team on Mount Huascarán.

Annie’s adventure cemented her status as “Miss Peck, the mountain climber.” But her fame didn’t translate into riches – she had $40 to her name. She spent 1905 trying to raise $3000 for another try at Huascarán, this time with mountain guides. She ended up with $700 and decided to try her luck with a shoestring budget. She made two attempts in July 1906 but both were doomed from the start.

Annie returned to New York knowing that she needed a fully funded trip for a chance at success. While Harper’s Magazine gave her $1000, most of her friends refused to donate – they wanted her to abandon her crazy goal. It wasn’t until Spring 1908 that a benefactor stepped up with the additional $2000 she needed.

One of Annie’s photos from her trek up Mount Huascarán.

Annie, her two experienced Swiss guides (Gabriel and Rudolf), and their porters carrying supplies arrived at the Huascarán base camp on August 6, 1908. Conditions were terrible. It took over a week to hike to the top of the saddle at 20,000 feet. They set out for the north peak summit on August 15, cutting steps in the ice for footholds. After eight exhausting hours, with at least another two to go, Annie decided to turn back. They arrived back in the village on August 17 to the news that everyone believed they had died on the mountain.

There was time for one more try. Annie hired 2 more porters and bought more warm layers, including a special pair of “outer” mittens. Conditions were much better, as a stretch of cold nights and sunny days had created a hard pack that was easy to traverse. They arrived at the base camp on August 28, made it to the snowline on August 30, and reached the top of the saddle on September 1 for a night of rest.

On 8:00am on September 2, Annie and the guides set out for the summit in high winds and extreme cold. Annie was grateful for her new face mask, and worried about her lost left outer mitten. As before, every step had to be cut into the ice. When they stopped for lunch at 2pm, Rudolf almost quit. After another hour of climbing, Annie’s left hand was nearly black with frostbite. She had to shake and rub it to get the blood flowing. They stopped to measure the altitude in a wind protected spot just below the summit, but their equipment was frozen. Their last steps to the summit were exhilarating but it was too cold to stay long. They were so cold and tired they fell several times on the descent.

On 8:00am on September 2, Annie and the guides set out for the summit in high winds and extreme cold. Annie was grateful for her new face mask, and worried about her lost left outer mitten. As before, every step had to be cut into the ice. When they stopped for lunch at 2pm, Rudolf almost quit. After another hour of climbing, Annie’s left hand was nearly black with frostbite. She had to shake and rub it to get the blood flowing. They stopped to measure the altitude in a wind protected spot just below the summit, but their equipment was frozen. Their last steps to the summit were exhilarating but it was too cold to stay long. They were so cold and tired they fell several times on the descent.

After the climb, Annie submitted the data she was able to collect to scientists in the United States, who estimated Huascarán’s summit was at 23,500 feet, which was higher than the world record held by a wealthy rival climber named Fanny Workman. Fanny then spent $13,000 ($300,000 today) on engineers to re-measure Huascarán, who calculated that it was 21,812 feet, less than Fanny’s record. Annie didn’t mind. For her the special challenge Huascarán’s cliffs and glaciers posed was enough – she had done something so difficult that nobody had ever done it before.

The Power of the Wand

Annie made mountain climbing an accessible goal for women and girls and she shared her stories to inspire them to follow in her footsteps. Illinois teenager Lucy Westlake just set her own climbing world record – at age 17, becoming the youngest female to climb the highest summits in all 50 states. She finished her quest on the top of Denali in Alaska on June 20, 2021 (Father’s Day!) with her dad.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Annie climbed her first mountain at age 32, while on vacation in the Adriondacks. When her group encountered a 6 foot high pile of downed trees blocking the path, everyone turned around except Annie and the guide. She followed him as he crawled over and through the trees and fell in love with the satisfaction she felt from conquering the obstacle.

Annie

Two years later, Annie embarked on her lifelong dream of traveling and studying in Europe. Annie often suffered from headaches and fatigue, and had tried many different cures. In Italy, a friend suggested they climb the 300 foot slope of Cape Misenum. The higher Annie climbed, the better she felt.

Annie wanted to stay in Europe and keep climbing, so she applied to the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, even though no other woman had ever attended. She spent the summer in Switzerland hiking on the foothills of the Matterhorn. She vowed to return and climb to its summit when she could afford the guides required for a successful trip. While Annie was in Athens, she hiked the surrounding mountains – some up to 3600 feet high – as often as possible. She developed a slow and steady pace. While she often lagged behind the group at the start, she had the most energy near the summit.

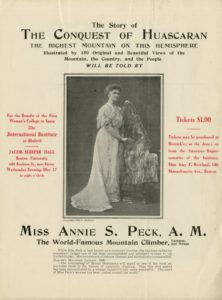

When she returned home, Annie needed a job that left her time for climbing. Inspired by her teenage admiration of adventurer and lecturer Anne Dickenson, Annie prepared a presentation about Greece and asked her influential friends to host living room chats. She built a reputation as an engaging and descriptive speaker and was soon selling out lecture halls around the country. Annie took time off every summer to climb.

By 1895, Annie had squeezed as much as she could out of her Greece lecture. She returned to Europe to climb the Matterhorn. When she arrived in Zermatt, Annie avoided the memorial to the first group to reach the Matterhorn summit – of the seven, four died in the attempt. After a week’s wait for good weather, Annie began her trek with nails in her boot soles for traction, layers for warmth, a veil to combat snow blindness, and a chocolate bar!

By 1895, Annie had squeezed as much as she could out of her Greece lecture. She returned to Europe to climb the Matterhorn. When she arrived in Zermatt, Annie avoided the memorial to the first group to reach the Matterhorn summit – of the seven, four died in the attempt. After a week’s wait for good weather, Annie began her trek with nails in her boot soles for traction, layers for warmth, a veil to combat snow blindness, and a chocolate bar!

She and her guides hiked to a climbers’ hut and rested until it was time to leave for the summit at 3:30am. They walked under the stars across the glacier and after two hours, reached the upper climbers’ hut. They ate breakfast there, gathering strength for what lay ahead – a narrow, steep path of sharp rocks and shallow hand and foot holds. They reached the 14,000 foot summit at 9:30am. That evening, she sent a telegram to the Boston Herald describing her climb, and while many papers carried the story, most of them focused on Annie’s decision to climb in pants instead of a skirt.

Back home, Annie filled lecture halls with the story of her Matterhorn climb while planning her next adventure. She settled on two Mexican volcanoes that no woman had climbed before: Popocatepetl “El Popo” and Orizaba. The New York Sunday World agreed to sponsor her trip in exchange for an exclusive and a photo of its banner on the peak.

When Annie arrived in Mexico in spring 1897, she spent time getting used to the altitude and gathered fellow climbers to join her. They started at El Popo, which was surprisingly easy to conquer. They left on April 20 at 5:00am on horseback, rode until they had to hike, reached the summit by 2:35pm, and returned to the village in time for a picnic dinner. The lack of hardship disappointed the World editor, who wanted more drama for the newspaper.

When Annie arrived in Mexico in spring 1897, she spent time getting used to the altitude and gathered fellow climbers to join her. They started at El Popo, which was surprisingly easy to conquer. They left on April 20 at 5:00am on horseback, rode until they had to hike, reached the summit by 2:35pm, and returned to the village in time for a picnic dinner. The lack of hardship disappointed the World editor, who wanted more drama for the newspaper.

Eight days later, Orizaba provided more excitement. Annie’s group traveled by mule through rain and slush up the slope to camp at Dead Man’s Cave. The next morning, under clear skies, they continued on mules until the ground got too rocky. Next was hours of steady climbing, up and over piles of lava rock covered with snow. At 12,000 feet Annie began to feel the lack of oxygen and could only take 70 steps at time. By 17,000 feet, it was 10-15 steps. With just 800 feet to go, she was so dizzy and nauseous that her guide pulled on the rope around her waist to help her to the summit. The way down was much more fun –Annie used a mat as a sled for part of the way!

The “Queen of the Climbers” famous photograph

When the official estimate came in that Orizaba was 18,000-18,600 feet, Annie claimed the world record for women in high altitude climbing. Annie maximized the publicity opportunity, posing for a studio portrait in pants and climbing gear that would be her trademark “Queen of the Climbers” photo for the next 40 years.

Annie’s next goal was Mount Sorata in Bolivia because nobody had done it before. It took a few years to get there and in the meantime, another climber beat Annie’s world record. When Annie finally began her trek up Sorata on August 3, 1903, she was accompanied by two Swiss guides and a U.S. government scientist. There was unseasonably deep snow. It took 5 days on mules just to reach a climbers’ camp at 15,850 feet. By then, the porters were exhausted and her companions were altitude sick. They had to turn back and it was too late in the season for a second try. Annie was bitterly disappointed -and then embarrassed to return home to stories in the papers about her assumed success.

The next year, Annie decided attempted Sorata again. This time she couldn’t afford guides, so went with another experienced climber. They started their trek on August 8, 1904 and Annie quickly regretted her choice of companion. Every time she wanted to proceed, he wanted to stop. Every route she suggested, he insisted on another one. They found a place to camp at18,000 feet and when they set out for the summit the next morning, Annie was overruled again on the path to take. After climbing 2500 feet, the men refused to go farther so Annie had to turn back too, lamenting “oh how I longed for a man with the pluck and determination to stand by me to the finish.” She decided to try her luck instead at Mount Huascarán in Peru.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Annie grew up in Providence, Rhode Island with her parents and three older brothers. While she was encourage to read and learn about “male” subjects like geography and science, her family had traditional views about the proper role of women in society.

Annie was 11 when the Civil War started and 15 when it ended. Annie attended lectures given in town by abolitionists and suffragettes, who toured the North to keep the public morale up. Annie’s favorite speaker was suffragette Anna Dickenson, who made her living on the lecture circuit talking about women’s rights and her mountain climbing experiences.

Annie was 11 when the Civil War started and 15 when it ended. Annie attended lectures given in town by abolitionists and suffragettes, who toured the North to keep the public morale up. Annie’s favorite speaker was suffragette Anna Dickenson, who made her living on the lecture circuit talking about women’s rights and her mountain climbing experiences.

Annie wanted to go to college, but her family said no. She visited a friend in Connecticut and enjoyed the freedom to make her own choices. She even danced – an activity forbidden at home. She finally returned home when she persuaded her parents to let her enroll in a teachers college near home.. Annie did well in the one year program, but there were no available teaching jobs in Rhode Island. She moved to Michigan to teach at Saginaw High School.

Annie wanted a four year college degree like her brothers – she believed it would open up the world to her like it did for them. She began searching for a college that would consider admitting a woman. Her first choice, Brown University – where her father and brothers had studied – would not. However, the University of Michigan had recently opened its doors to women, and its president was a Brown alum and friend of Annie’s dad. He advised Annie to take a few months off from work to study for the entrance exam to the Classics Department.

Annie’s University of Michigan portrait 1878

Her parents said no to college at first, telling her that at age 27, she was too old and should come home to find a husband. Annie persisted, and her dad finally conceded after she asked him “why you should recommend for me a course so different from that which you pursue, or recommend to your boys?”

Annie started at Michigan in 1874. She loved it there, particularly because she was treated no differently than her fellow male students. She majored in Greek and Classical Languages, earning a Bachelor’s degree in 1878. But the opportunities she hoped would materialize after she had a college degree didn’t – she taught two more years of high school and then returned to Michigan to earn her Master’s degree in 1881. She got a teaching position at Purdue University She moved home in 1884 to being planning the next phase of her life, which centered around getting to Europe as she had always dreamed of doing. “I am going to Europe because I wish to and am able.”

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Annie was born October 19, 1850.

- Annie never married and lived in hotels or with family and friends in between her travels. Her motto was “Home is where I put my trunks.”

- Annie died July 18, 1935.

- Annie was fluent in Spanish, Portuguese, French, and German.

- Annie wrote four books, including The Search for the Apex of America: High Mountain Climbing in Peru and Bolivia, including the Conquest of Huascaran, with Some Observations on the Country and People Below; Industrial and Commercial South America; The South American Tour: A Descriptive Guide, and Flying Over South America: Twenty Thousand Miles by Air.

- In 1911, at age 60, Annie traveled to Peru again to climb Corupuna, which was rumored to be higher than Huascarán. Although it proved to be shorter, Annie celebrated her trip to its summit by planting a banner that said “Joan of Arc Equal Suffrage League – Votes for Women” at the summit.

- Annie marched in the May 4, 1912 New York Womens’ Suffrage Parade and brought the Joan of Arc Suffrage banner that she had taken with her to climb Corupuna. Annie was elected president of the Joan of Arc Suffrage League in 1914.Annie made her sixth trip to South America in November 1915, this time on a lecture tour sponsored by U.S. companies who wanted to advertise their products there. While she didn’t climb any mountains, she did zip line across a river in Brazil.

- In her 70s, Annie started a new venture escorting groups of people to South American as a tour guide. The Geographical Society of Lima named the North Peak of Huascarán “Annie’s Peak.”

- On November 1929. Annie embarked on 7 month, 20,000 mile tour of South America by air on the new Pan Am Airways. Her trip was sponsored by various governments as part of encouraging tourism in their countries. In 1930, the Chilean government awarded her its Decoration of Merit.

- Annie climbed her last mountain, Mount Madison in New Hampshire, when she was 82.

- Amelia Earhart wrote a blurb for one of Annie’s books, stating that “I am only following in the footsteps of one who pioneered when it was brave just to put on the bloomers necessary for mountain climbing.”

Want to Know More?

Kimberley, Hannah. A Woman’s Place is at the Top: A Biography of Annie Smith Peck, Queen of the Climbers (St. Martin’s Press 2017).

Eschner, Kat. “Three Things to Know About Pants-Wearing Mountaineer Annie Smith Peck” (Smithsonian Magazine October 19, 2017).

Living on Earth Magazine Staff. “Annie Smith Peck” (Public Radio Feb 6, 2018).