Health Hero

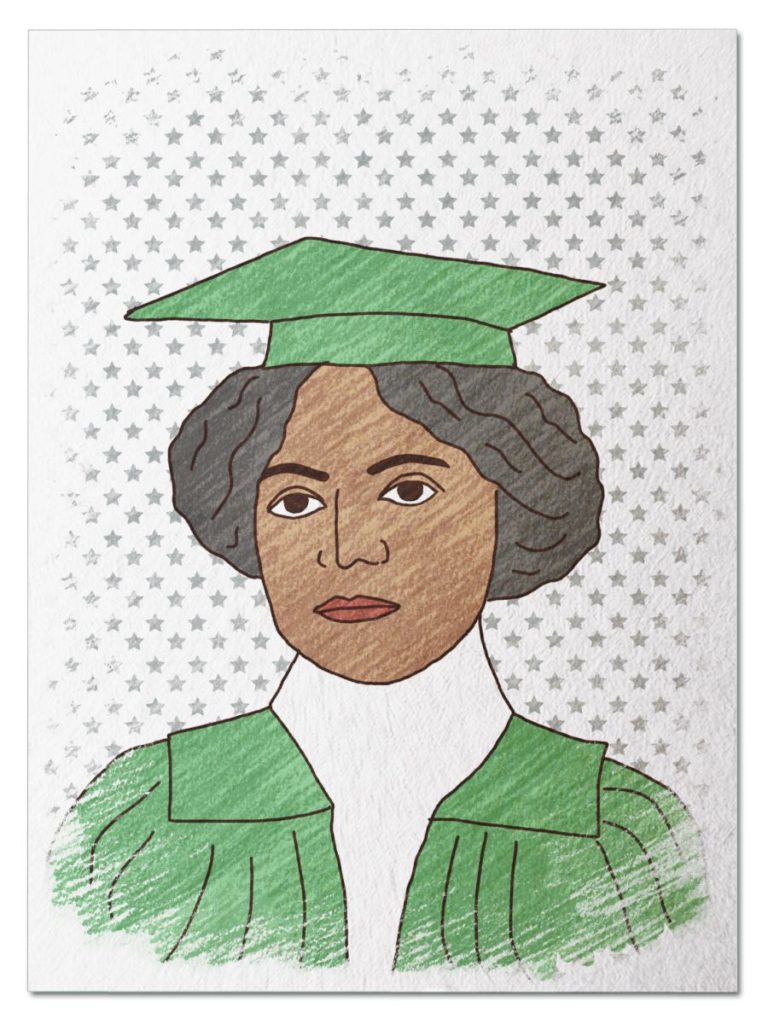

She created the first effective treatment for leprosy as a 23 year old chemistry professor, but was erased from history when the head of her department took credit for the work himself. Travel back to her 1915 University of Hawaii laboratory and meet Alice Ball …

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Alice Ball inspected the light colored liquid in her test tube. Then, she placed a drop into water and swirled it around. She smiled as the two liquids mixed together. It was 1915 and Alice just created the first effective treatment for leprosy — an injectable oil extract from the seeds of the chaulmoogra tree. And she was only 23 years old.

Bottle of Chaulmoogra Oil, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History

Chaulmoogra oil had been used to treat skin conditions in eastern medicine since the 1300s. The problem was that there was no good way to administer the oil. It was difficult to apply topically because it was so sticky. It was too painful to inject under the skin because it caused blisters. And the taste was so horrible that it made people sick.

Alice knew that the oil had to be injected into the bloodstream to be effective. But it was dense and couldn’t mix with human’s water-based blood. The oil had to be chemically altered to become water-soluble. And Alice was determined to figure out how. So for more than six months, she conducted experiments with the oil in the University of Hawaii’s laboratory.

Alice was convinced she could create an effective treatment by isolating the active ingredients in the oil. She separated the fatty acids from the oil, then converted the fatty acids into a water soluble mixture through the ester process (a reaction between acid and alcohol). Alice ended up with an extract that could be injected into the body and absorbed through the bloodstream. It was a medical breakthrough.

Over the years, Alice’s new treatment improved the lives of thousands of people who were diagnosed with leprosy. It allowed some of them to be treated at home, rather than isolated in a hospital or asylum. By 1918, certain patients could live with their families once again without fear of infecting others. In fact, over 80 patients in the infamous Kalihi Hospital on Oahu were able to return home because of her invention.

Over the years, Alice’s new treatment improved the lives of thousands of people who were diagnosed with leprosy. It allowed some of them to be treated at home, rather than isolated in a hospital or asylum. By 1918, certain patients could live with their families once again without fear of infecting others. In fact, over 80 patients in the infamous Kalihi Hospital on Oahu were able to return home because of her invention.

Alice never received credit for her ground-breaking experiment — she died before she could publish her results. Arthur Dean, president of the University of Hawaii and a fellow chemist, continued Alice’s work. He published the findings but didn’t mention Alice, therefore taking credit for her work. In fact, the process for creating the extract became known as “Dean’s Method.” Dr. Dean went on to benefit from her discovery by mass-producing the injectable treatment.

Alice’s mentor, Dr. Harry Hollman, tried to set the record straight in 1922. He renamed her process “The Ball Method” in a medical journal. Despite his efforts, however, Alice was forgotten by the world for many years.

The Power of the Wand

Alice made the world a better place through her tenacity in the laboratory. Her invention was the standard treatment for leprosy for more than 30 years, until effective antibiotics were developed in the 1940s. In fact, its still used today in very remote locations of the world.

After 80 years, the history was finally corrected. In 2000, the University of Hawaii placed a plaque on the campus’ only chaulmoogra tree in her honor. It was the exact same tree that Alice used in her experiments. The University also awarded her the Regents’ Medal of Distinction posthumously in 2007. The state of Hawaii has honored her as well — every four years, Hawaii celebrates “Alice Ball Day” on February 29.

Since Alice’s time, many women have broken barriers in the fields of STEM. For example, 17-year old Anushka Naiknaware invented a new bandage to help wounds heal faster. Her invention earned top marks at the Google Science Fair and the Lego Education Builders Award in 2016, when she was still in middle school. Anushka’s bandage has sensors that monitor the moisture, which allows caregivers to determine when it needs to be changed. And it has the potential to improve the lives of thousands of people.

Her Yellow Brick Road

When Alice started graduate school at University of Hawaii in 1914, leprosy was a major public health concern on the islands. It’s thought that the disease was introduced to the islands by immigrants in the 1800s. After that, it was hard to prevent its spread. So anyone diagnosed with leprosy had to live permanently at the leprosy colonies on the island of Molokai. Both the Kalawao Colony and Kaluapapa Colony were managed by the Hawaii Department of Health, with Catholic priests and nuns providing care to the patients.

Leper Colony on Molokai Island, Hawaii, National Park Service

Hansen’s Disease (AKA leprosy) is one of the oldest recorded diseases in the world. For most of history, it had no cure or treatment. As a result, there was a lot of fear about the disease. Most people with leprosy were banished from their community and lived in complete isolation.

Alice grew interested in potential leprosy treatments while in graduate school. In fact, her master’s thesis was about the kava plant and its potential therapeutic treatments for leprosy (it was used by patients to ease the pain).

Alice was a trailblazer — she was both the first woman and the first African American to receive a master’s degree from the University of Hawaii. Then, she was offered a teaching position and became its first female chemistry professor.

Alice was a trailblazer — she was both the first woman and the first African American to receive a master’s degree from the University of Hawaii. Then, she was offered a teaching position and became its first female chemistry professor.

After graduation, Alice was contacted by Dr. Harry Hollman, director of the leprosy clinic at Kalihi Hospital in Honolulu. He had heard about her graduate work. And he was intrigued. Specifically, Dr. Hollman wondered if the technique that Alice developed in her master’s thesis could be used to develop a cure for leprosy. So he asked her to experiment with the fruit of the chaulmoogra tree. And she agreed to give it a try.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Antique chemistry lab stand with glass beakers

Alice grew up being surrounded by the wonders of chemistry — her family included some pioneers in photography. Her mother, Laura, was a well-respected photographer and installed a dark room in the house. Her father, James, owned a photography studio with her grandfather, J.P Ball. In fact, J.P. Ball was one of the first African Americans to learn, an early form of photography. Alice didn’t join the family photography business, however. She had something bigger in mind.

Alice wanted to go to college. And her parents supported her all the way. Back then, many black women worked as domestic servants — few graduated from high school, much less college. Alice studied at the University of Washington and received degrees in both pharmaceutical chemistry and pharmacy. Then, she was offered a scholarship to pursue her master’s degree at the University of Hawaii. And she couldn’t pass it up.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Alice was born on July 24, 1892 in Seattle, Washington. She was one of four children, with two older brothers, William and Robert, and a younger sister named Addie.

- Alice graduated from Seattle High School in 1910. Then, she graduated from University of Washington with a pharmaceutical chemistry degree in 1912 and degree in pharmacy in 1914.

- Alice went to the University of Hawaii for her master’s degree. She even published a scientific paper in the Journal of American Chemical Society when she was 21 years old. Her paper was called “Benzoylations in Ether Solutions.”

- Alice died in Seattle on December 31, 1916, at age 24. Legend says that she died from chlorine poisoning from an accident in her laboratory. However, her death certificate lists tuberculosis as the cause of death.

- Alice was rediscovered in 1977 by Dr. Kathryn Takara, who came across her name in the University of Hawaii archives.

- In March 2016, Hawaii Magazine named Alice as one of the most influential women in Hawaiian history.

- A short film about Alice, The Ball Method, was released at the Pan African Film Festival in February, 2020.

- From 1866 to 1969, over 8,000 Hawaiians with leprosy were required to live in isolation on the island of Molokai. The state finally reversed its policy after effective antibiotic treatments were developed and could be given on an outpatient basis.

- After it closed, the state of Hawaii allowed anyone currently living there to stay indefinitely. In fact, there are still a few elderly patients who live in Kaluapapa today. Now, most of the land is a national historic park.

- Hansen’s Disease (AKA leprosy) is still a problem today, especially in poor countries. Its curable with a combination of drugs, but the treatment is expensive. The World Health Organization provides treatment for free in some countries.

- About 16 million people worldwide have been cured of leprosy in the last 20 years.

- World Leprosy Day takes place on the last Sunday of January every year.

Want to Know More?

“Alice Ball scholarship honors pioneering chemist in fight against Hansen’s disease,” University of Hawaii News, February 23, 2017 (accessed at https://www.hawaii.edu/news/2017/02/23/alice-ball-scholarship-honors-pioneering-chemist-in-fight-against-hansens-disease/).

“Alice Augusta Ball,” National Society of Black Physicists, February 2, 2019 (accessed at https://www.nsbp.org/nsbp-news/bhm-physics-profiles/2019-honorees/121-alice-augusta-ball).

“Meet the Chemist Who Engineered the First Effective Treatment for Leprosy,” Massive Science, May 26, 2017 (accessed at https://massivesci.com/articles/meet-the-chemist-who-engineered-the-first-effective-treatment-of-leprosy/).

John Parascandola. “Chaulmoogra Oil and the Treatment of Leprosy.” Pharmacy in History, Vol. 45, No. 2 (2003) pp. 47-57 (accessed at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277597573_Chaulmoogra_Oil_and_the_Treatment_of_Leprosy).

Harry T. Hollmann, “The Fatty Acids of Chaulmoogra Oil in the Treatment of Leprosy and Other Diseases,” Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology, Vol. 5 (1922) pp. 94-101 (accessed at https://zenodo.org/record/1496183#.XmfSji2ZNmA).

Susan Kreifels, “Alice Ball Made a Stunning Find in Her Early 20s.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin. February 18, 2000.

Susan Kreifels, “Ground Breaking African-American UH Chemist Finally Recognized.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin. March 1, 2000.